On August 3rd I trotted into Garnet Canyon and soloed the should-be-classic Dike Route on the Dike Pinnacle. While the climbing itself was excellent, the direct descent into Garnet Canyon from the summit of the Dike Pinnacle nearly killed me… metaphorically… of course.

After a magical onsight solo outing on the Chouinard Ridge (5.5, II), I once again packed up the rock shoes and chalk bag for a solitary Grand Teton National Park outing. My mission du jour’ was the Dike Route (5.6, IV), a unique climb following a striking 3000 foot diabase intrusion on the Middle Teton’s eastern sub-peak, the Dike Pinnacle. Save for a few rare climbs on these dikes throughout the range – the other most prominent, yet seldom visited, of which can be found on Mount Moran – Teton alpine rock climbing takes place on granite of various compositions. The diabase of which these dikes are composed presents foreign climbing styles diametrically opposed to the smooth slabs, edging, and vertical cracks of Teton granite, sporting horizontal fractures, generally positive holds and interesting geometric blocky climbing similar to basalt. Bobbi Clemmer and I climbed the Dike Route with a rope in 2022, and since then I’ve loosely been toying with the idea of returning sans cord. Although the climbing does get unnervingly steep for the grade at points, the generally stellar rock quality and overwhelmingly positive holds provide confidence. I had never intentionally soloed 5.6 before, yet also figured I could downclimb from the crux pitch if I wasn’t feeling it, with the proceeding pitches clocking somewhere around 5.4. And alas there I was, alone in the park again.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

From the second I left the Lupine Meadows trailhead something was off. By 7:00AM the heat was already escalating, accompanied by smoky lung-taxing air. Every step up the crushing Garnet Canyon switchbacks produced clouds of dust. We needed rain. Sweat poured from my shirtless dirt stained body as I bumbled into the Meadows halfway to heat stroke. I didn’t really want to continue, yet my first sight of the beautiful black vertical gash cleaving the lower buttress of the Middle Teton had too much allure. Within an hour I was kicking steps up an unexpected, yet thankfully short lived, 40 degree snowfield without crampons or an axe, using hand held talus daggers for a crude means of traction. I reached the dike itself by 10:00AM and hastily began my pilgrimage to the sky, fearing the ever warming rock. 300 feet of wandery 5.4-ish slab climbing on pleasant edges saw me to the crux pitch, marked by a janky webbing anchor between two far spaced pitons. I remembered the stemming sequence right above the anchor feeling insecure in approach shoes two years ago, but today I had my ninja slippers. One tricky highstep on positive but small holds led to an awkward mantle and a nice ledge for a shoes-off snack. To this point climbing temps had been quite pleasant, but the early August sun was beginning to crank up its attitude, and of course I had picked the only rock climb on exclusively black stone within ten miles. My toes started swelled as sweat poured from my brow on what would ultimately be the hottest day of summer. Thank goodness I had a surplus of chalk.

Above my perch lurked a solid 200 feet of near vertical climbing on wild fractured blocks which initially appear totally detached and deadly, yet somehow are glued together by the rock climbing gods. The climbing on this next pitch is very geometric and nondescript, requiring large moves between jungle gym holds and a fair bit of route finding spidey-senses. At times I would clamber up a crack only to find unreasonably difficult climbing and reverse course. The Dike itself is about 40 feet wide, so any given horizontal band presents a plethora of confusion. By the time I hit the second crux, two steep slabs with small crimps and edges near the top of the dike with 700 feet of clean air below, my toes were swelling to maximum capacity and singeing with pain. A few technical maneuvers forced me to trust my feet like I never have before without a rope, but ultimately, just as expected, fell flawlessly. 100 feet of glory slab climbing brought me to the conclusion of the fifth class climbing and a nice canopy of small pines to rest. The 600 feet of steeper initial dike were complete, and now only a trivial 1700 feet of mountainous fourth class remained. I offer trivial with extreme sarcasm.

On the upper mountain the dike eases off into standard unroped “mountain terrain”, weaving between third, fourth and low-fifth class terrain en’ route to a beautiful, seldom visited, 12,400 foot summit. Two parties dotted the classic Buckingham Ridge on the Middle Teton, and several others gathered atop the Middle Teton summit almost certainly via easier routes on the southwest and north faces. On the Dike Pinnacle I was all alone. I popped off my shoes and made a padded lounge with my shirt and jacket for some sunbathing on a particularly smooth granite slab. The Dike Pinnacle is one of my favorite summits in the park, for no reason other than my uncanny affinity for atypical summits, routes and descents that are equally awesome as the classics, yet somehow fly beneath the radar. I first visited the pinnacle in 2022 with Bobbi, and returned this past winter for my first ski descent via the East Ridge and Southeast Couloir. I built a small cairn from some convenient plates and spent a few moments reflecting on my father who passed away in these mountains seven years ago. I put his, and now my, favorite hat – Key Polymer being the epoxy company he worked at for my entire childhood – on the cairn. For whatever reason his presence was especially significant today.

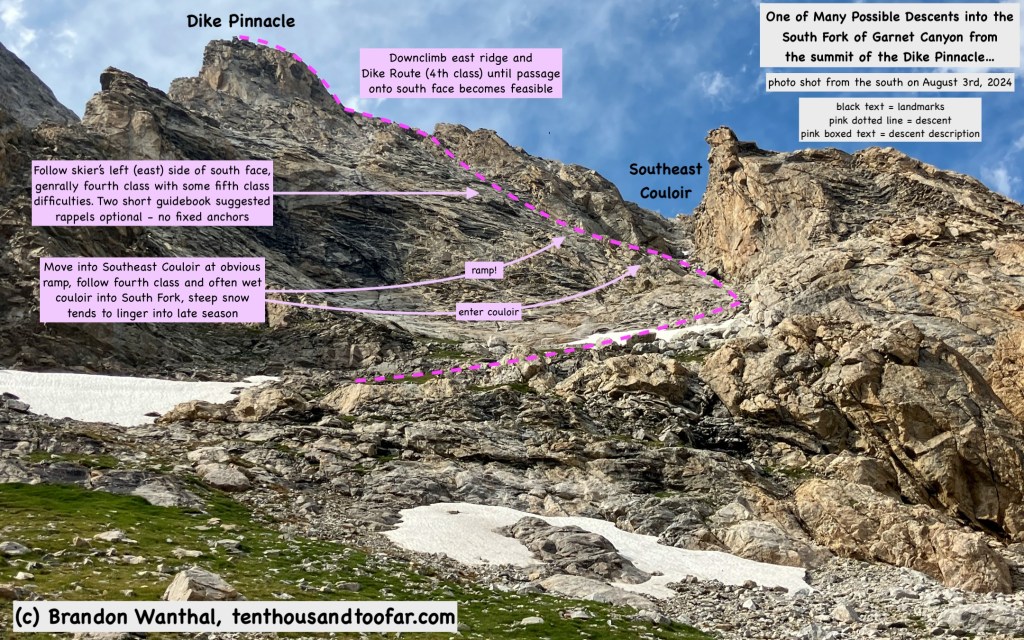

Because of my reluctance to carry the 60 meters of rope needed to rappel into the notch separating the Dike Pinnacle from the Middle Teton, and down-climb the dubious 5th-class stone on the west face between the rappels, I opted to retreat directly into the south fork of Garnet Canyon (more information on the continuation to the Middle Teton summit can be found here). The Ortenburger-Jackson guidebook offered a crude route into the canyon via the east ridge and either the Southeast Couloir or south face – the latter wasn’t exactly clear. Hours later I was still onsighting the mess of steep, loose and unsuspectingly technical terrain, cursing the guidebook for suggesting such a serious descent route with vague, if not casual, language. The book suggested two optional rappels to pass large chockstones, yet I found no signs of anchoring and was able to down climb the fifth class difficulties around both distinct obstacles. In hindsight I basically descended the eastern extremity of the south face along a shallow couloir until a ramp system provided a convenient traverse east into into the Southeast Couloir. In the larger Southeast I was greeted by widespread lingering isothermal snow. Although I had found an old ice axe on the south face, this snow was a bit too steep and consequential without crampons, and a bit too soft for reliable self arresting. Some slippery chimneying between the robust snow flank and exposed rock led to a chossy and wet lower couloir, and because of my reluctance to touch any more snow I opted for a rock detour around a lower snowfield that involved some exposed onsight 5.6-ish down-climbing on fortunately stellar, avalanche polished, granite. I reached the South Fork approximately 2.5 hours after leaving the summit, thoroughly dehydrated and ready for just about anything besides mountain climbing.

My return to terra-firma involved a sour attitude at the hands of aching knees interspersed by a few pleasant conversations with curious climbers. All in all this day was a net positive, yet tainted significantly by blazing heat and a tenuous, if not dangerous, descent. When leaving the car I was mentally preoccupied by the initial 600 feet of 5.6 soloing, but ironically that segment was the easiest of the day. However, all things considered I was satisfied with another long solo outing in the greatest national park on Earth. Unlike the Chouinard Ridge I didn’t return with much spiritual insight. This day held a more grizzly “grind-it-out” tone which left me beaten, battered and bruised for the week ahead. On one hand I blamed myself for not forecasting the likely, if not obviously, tumultuous descent into the South Fork. On the other hand, the Tetons are rugged mountains rife with surprises around every corner – this I knew – and thus, days like this really are just par for the course. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger… they say. Rotator cuff update: we’re on the right path.

Resources:

- Dike Route Trip Report, 2022 (tenthousandtoofar.com)

- Teton Rock Climbs (Aaron Gams) – guidebook

- A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range (Ortenburger, Jackson) – guidebook

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Range Meal Bars, The High Route, Black Diamond Equipment and Barrels & Bins Natural Market.

enter your email to subscribe to new article updates

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading

Leave a comment