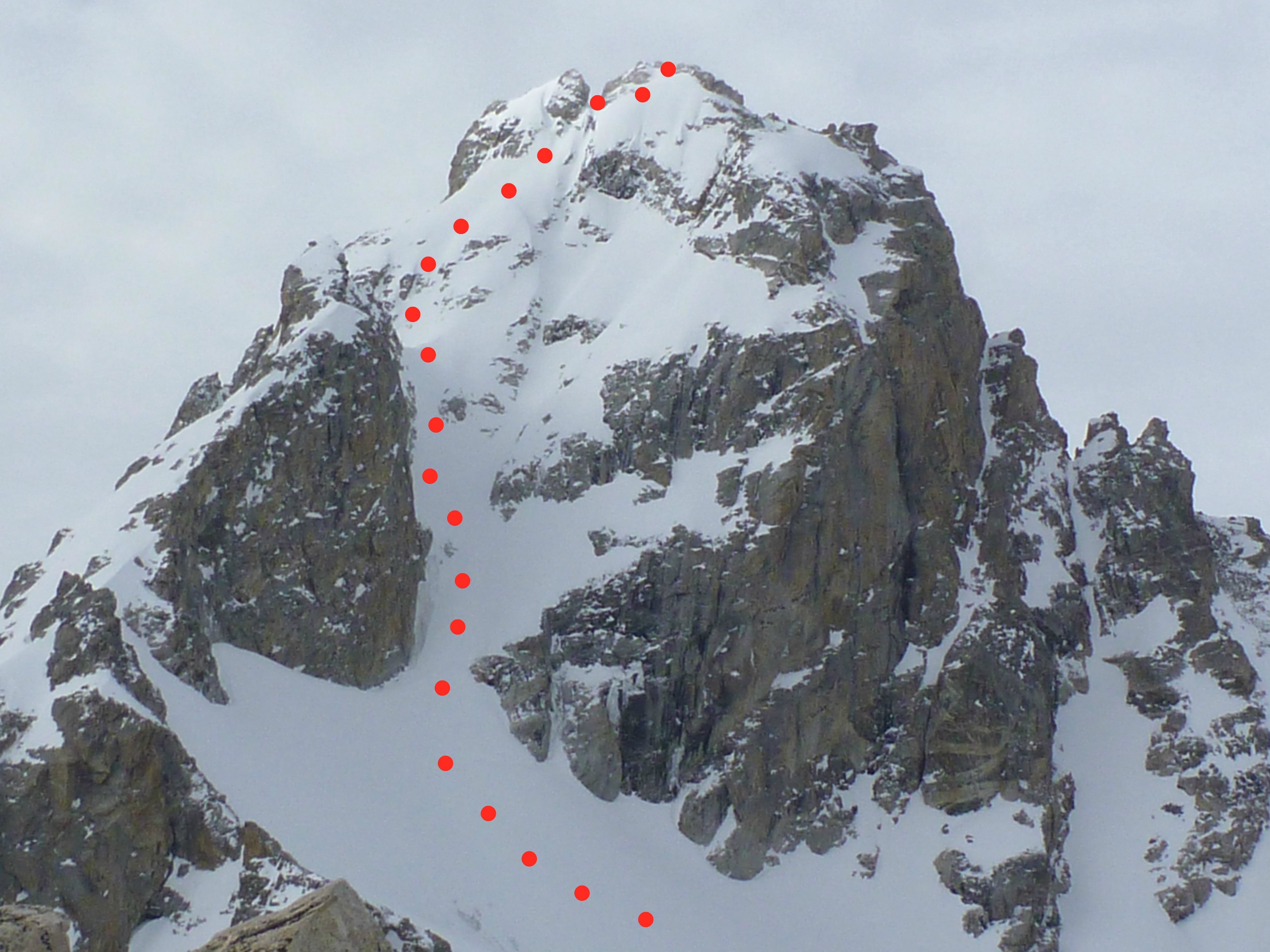

The East Face/Glacier Route (we’ll refer to it simply as the East Face) of the Middle Teton is one of three Teton ski lines listed in Chris Davenport and Art Burrows’s “50 Classic Ski Descents of North America.” Coupled with Mount Moran’s Skillet Glacier and the Grand Teton’s Ford-Stettner Couloir, it’s among excellent company. Unlike many other Teton faces, this line stays hidden to the naked eye, only coming into sight when viewed from high-points to the north, most notably, the Grand Teton. A decent length shot by Teton standards, the East Face is a complex line that breaks nicely into three unique sections. Part one – highly exposed, fifty degree fall-line face skiing over unrelenting cliffs with a few hairy traverses. Part two – slightly less steep and much less exposed turns in a north facing gully that regularly holds excellent snow. Part three – low angle party skiing out the infinitely wide Middle Teton Glacier into Garnet Canyon. Link all three components together and you have the perfect recipe for an epic day in the mountains. The East Face of the Middle Teton was my first Teton classic – below is the refurbished edition (with plenty of relevant beta) of my original 2018 post – enjoy!

This will be my third full year in the Tetons, and after a generous winter brought over 500 inches of snow, sunny skies have me itching for bigger objectives. The Middle Teton, at 12,805 feet, is the third tallest peak in the Teton Range. From my home in Victor, Idaho, the Grand, Middle and South Tetons have teased me the last four years. I got out for a few mid-winter missions in Grand Teton National Park, putting ski turns on Disappointment Peak, Shadow Peak, Albright Peak and 25 Short, but nothing overly notable. Facing a narrow weather window after a nasty Mid-April storm cycle, it was time to finally crack the 12,000 foot barrier. I climbed the Middle three summers ago, so I sided with familiarity. I headed to the Taggart Lake parking area the day before, just in time for sunset. I talked with several other skiers car-camping that evening, but none had ventured into the high alpine. The forecast bode clear skies and valley temperatures of nearly sixty degrees, and the Middle is set deviously far back in the range, so an early start was imperative. I set my alarm for 3AM and curled into the trunk of my new Hyundai Elantra, anxiously anticipating the day to come.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Used it to fuel an amazing adventure? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

The Approach

I didn’t even make it to three. Maybe the nerves were to blame… maybe the cold… either way, I awoke naturally at 2:45AM and immediately fired a pot of coffee. By 4:00AM I was skinning through low-lying forest on my way to Garnet Canyon. A group of four was ahead, and a group of two followed behind, all headed for the same objective. I was overjoyed to find Taggart Lake still frozen. Come May skiers often have to bushwhack the shores, taxing lots of precious time. From here I began the tedious approach up Garnet Canyon to Lupine Meadows, the heart of the range. Surrounded by the Grand, Middle and South Tetons amongst many others, Lupine Meadows is an amphitheater of towering granite peaks wrapping climbers on three sides, filled with inspiration, mystery and awe. Right on cue, pre-dawn light illuminated the Middle Teton ever so slightly, just enough to make the hair on my neck stand up.

After a thorough refueling I veered left and began climbing the saddle separating the South and Middle Tetons. At this point I was still planning to ascend and descend the Southwest Couloir, strictly out of familiarity. I recognized the route from my previous journey and made solid pace up the first headwall. I followed the skin track from the group ahead, and before long overlapped them transitioning from skins to boots. Two from their party had opted for the South Teton, leaving just three of us prospecting the Southwest Couloir. During our changeover the clouds gradually lifted, revealing a direct gully to the summit. I stashed my skins, strapped on my Petzl Leopard crampons and grabbed a quick snack in preparation for the climb ahead. Tom, Henry and I decided to ascend together, and began kicking steps towards the couloir.

A mostly stable, re-frozen snow-pack provided great traction. The day was warming significantly by 8:30AM, fixating us on summiting as soon as humanely possible. At the crux of the couloir I leap-frogged ahead, busting a thin trail through a body-width choke studded with loose rocks. The higher we climbed the more unstable the snow became, turning to a reactive wind crust around 11,500 feet. We held congress briefly, deciding to continue upward with greater spacing to mitigate avalanche hazard. After negotiating a few dicey cliff bands we regrouped and followed Henry’s lead to the summit. The view into the Southwest from the summit was all time, and sights of the range beyond were plain and simply humbling.

The Descent

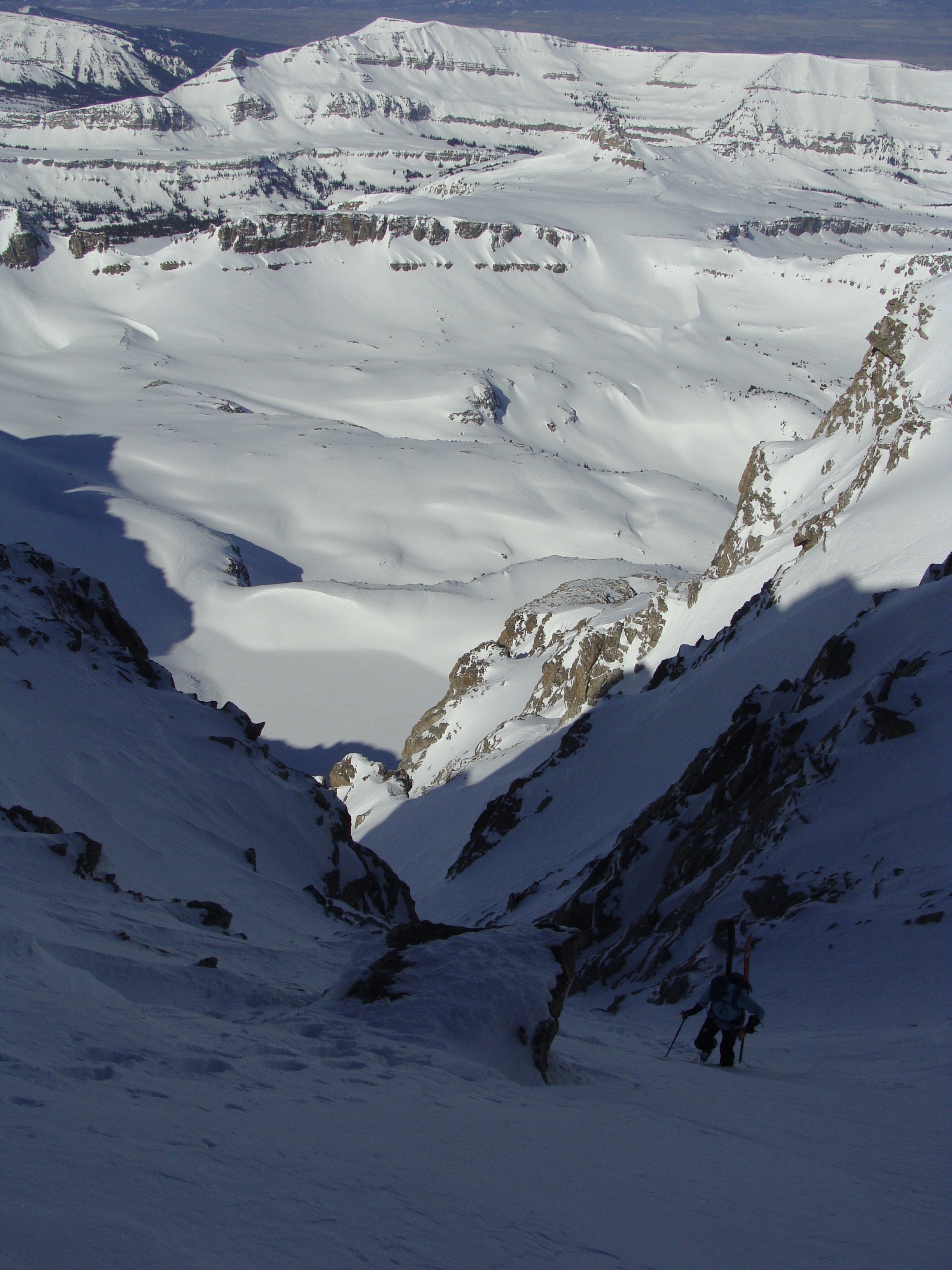

Initially I had planned on retracing my steps, but a combination of wind-hammered snow in the Southwest Couloir and the differing plans of my newfound partners changed my course. Tom and Henry planned to ski the East Face, a high-consequence line terminating at the saddle between the Middle Teton and one of it’s spires, the Dike Pinnacle. From there they would veer north onto the Middle Teton Glacier, and follow the “Glacier Route” into the north fork of Garnet Canyon. With a brand new, never before skied pair of Black Diamond Link 90’s on my feet, my first ever pair of ultra-light mountaineering skis, I wasn’t oozing with confidence. New skis have kinks to break in, just like running shoes and girlfriends. However, the allure of a “50 Classic” was just too much to pass up. After receiving their blessing I piggybacked Tom and Henry’s mission, shimmying onto the wildly exposed upper East Face. Tom and I opted for the popular down-climb to the notch south, traversing knee deep snow above a swath of cliffs. Flirting with fifty degrees, this was no place to fall. Step by step we jammed our crampons and axes into the snow, and after a few heart-pounding minutes we jumped safely into the notch. Henry opted to ski the traverse – a bold decision indeed. Clicking into my skis above the East Face I struggled to suppress the nerves. I was staring down, by far, the biggest line I’d ever skied.

The line was just as I imagined it to be, exposed, steep and sun affected. Henry dropped in first, inching down above a thin cliff band and straight-lining into the East Face. He was about as bold a skier I’d met in the back-country. I tentatively followed suit and was happy to find a manageable crust on my first jump turn. I worked my way down the face cautiously, looking uphill every available moment to inspect the snow. I methodically hacked my way to the Dike Pinnacle, the first “safe-zone” on the face. I was a bit too fused with adrenaline to appreciate our feat, and with at least 1,000 feet of steep snow to go, the party was far from over.

Boot deep powder awaited us above the glacier, a reward for tackling the burly East Face. Second by second I released tension in my legs, progressively cranking the pace with many hoots and hollers into Garnet Canyon. I just couldn’t believe it, after all the manky affairs above, we were skiing blower powder off the third tallest Teton peak! The lower we traveled the heavier the snow became, eventually morphing to barely-skiable cream cheese in Garnet. The day was balmy, a sweltering 50 degrees, and while we all appreciated the summer-like weather to accompany our sandwiches, we were equally grateful to be off the Middle before avalanches got the chance to simmer. In the next fifteen minutes a few slides released on the Grand and Middle alike, raining gloppy concrete thousands of feet into the canyon below. If there’s one motto to keep front and center for springtime alpinism it’s the classic “start early, finish early.”

The Numbers:

- Trip time: 7-9 hours (car to car)

- Summit Elevation: 12,805 feet

- Prominence (from lower saddle): 1,125 feet

- Vertical on East Face: 1,044 feet

- Vertical on entire route: 2,000 feet (appx.)

- Total vertical gain: 6,500 feet (appx.)

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Range Meal Bars, The High Route, Black Diamond Equipment and Barrels & Bins Natural Market.

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.