On Sunday November 8th I climbed my 2025 dream route, onsighting every pitch of Rock Warrior (5.10b, 6 pitches, 800′), an old school ground-up psychological testpiece on the storied Black Velvet Wall of Red Rocks Canyon. I was joined by Bobbi Clemmer and Joy Seward, who both proudly flashed the route. This was among the best climbing days of my life.

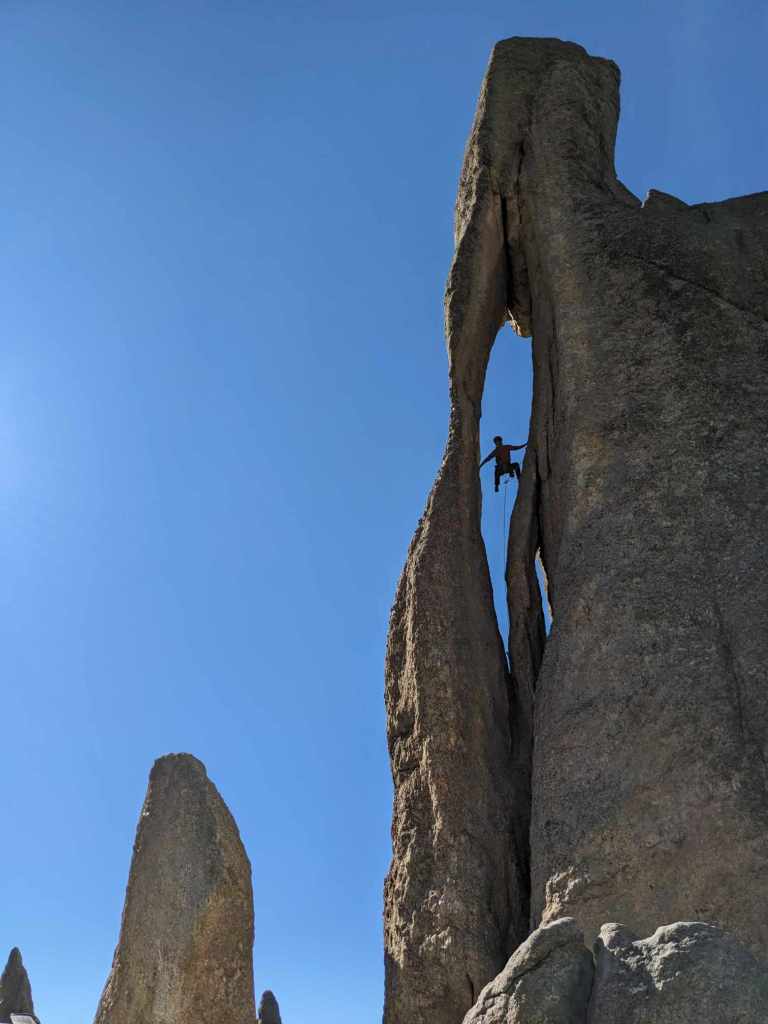

On the left margin of the dazzling Black Velvet Wall, home to the world famous Epinephrine (5.9, IV), is an equally licentious and disorienting 800 foot buttress of undulating Navajo Sandstone and Desert Varnish harboring two classic routes with a sinister reputation – Rock Warrior (5.10b R) and Sandstone Samurai (5.11a X). Both routes were established by the “Adventure Punks”, a clique of 1980’s era renaissance hardmen with a reverence for the waning art of ethically pure and unapologetically bold traditional climbing. Rock Warrior was the first route established on the wall, boasting a mere 13 lead bolts in 820 feet. According to legend, the route was an intentional statement against the heavy handed bolting tactics of “certain beloved Red Rocks first ascentionists”. One year after Rock Warrior, the prolific and bolt-happy Jorge Urioste, Joanne Urioste and cohort installed the stainless steel highway Prince Of Darkness, a mere lemon toss to the right. With 12-16 bolts per pitch and a nearly identical climbing style, Prince of Darkness couldn’t be more different than Rock Warrior. When the Adventure Punks caught word of Prince of Darkness, they decided to up Rock Warrior’s ante with Sandstone Samurai, an even more severe visionquest at the staggering grade 5.11a X. As a climbing history connoisseur cut from the adventure laced cloth of Teton alpine climbing, with a history of heady traditional climbing in Joshua Tree, Idyllwild and the South Dakota Needles, I was immediately captivated by the dichotomy between these three Black Velvet routes.

My first climbing in Red Rocks occurred in the early summer of 2025. Without an immediate partner I quickly took to free soloing the many long slab and face routes of First Creek Canyon. I found the sandstone friendly and intuitive. My first partnership was with an off-duty mountain guide and desert 5.13 crusher. Why he bothered to climb with my puny 5.10 arms I’m still not sure, but over July we knocked out three long, challenging and memorable Red Rocks routes. Among them was Risky Business (5.10c, 4p, 400′), a traditional face climb of similar style to Rock Warrior and Sandstone Samurai, on the immaculate varnished panel adjacent to the famed Dark Shadows. Risky cataclysmically shifted my trad climbing paradigm. The route is beyond imposing – so steep, so blank – with no obvious features longer than a pair of 30 foot incipient cracks 300 feet off the ground. If I’d been doing the first ascent, I’d have rucked 40 bolts to the summit of Mescalito and rappelled in. Well, there’s only nine lead bolts and one fixed pin in 400 feet. Thin, crafty and cryptic traditional gear placed in inconspicuous seams, a steady head, and steely enough fingers to puzzle out a sea of vertical 5.10 crimping without ripping, gets you to the top. As an alpine granite boy, most of my trad climbing has tackled soaring crack lines visible from miles away. The ground-up face climbing of Southern California, protected by bolts drilled from no hands stances, also made sense to me. But routes like Risky Business and Rock Warrior were new and exciting. Following the path of least resistance isn’t enough. Instead, these routes are a high stakes game of hide-and-seek. 99% of the patina plates and shallow breaks on these inky black headwalls won’t take protection. But occasionally a nickel thin ballnut slot, constriction for an offset wire, or horizontal break for a finicky cam reveals itself. The game of leading such routes is not only staying “on route” and resisting falling, but maintaining a vigilant eye for vague protection opportunities, and having the niche experience to capitalize on them. I’ve only been climbing five years, but traditionally protected desert varnish face climbing seems like the ultimate test of a well rounded trad climber.

After onsighting Risky Business without excessive trial or trepidation, I was keen to push my limits. Of the thousands of multi-pitch traditional climbs in Red Rocks, only a handful suit the uncompromising purity and adventure-first ethic set by the Adventure Punks. And of them, Rock Warrior was the obvious next step. While rated one letter grade easier than Risky, it was twice the length and notably more runout. 5.10b was also a perfect grade for my special lady, who would love following such a wild and classic line. My 2025 dream project was hatched: to lead and onsight every pitch of Rock Warrior. But first, I would need to prepare. Routes like Rock Warrior favor the overqualified. My goal was not only clipping the chains on each pitch, but feeling confident, competent and controlled the entire way.

“In doing this route (Rock Warrior), the first ascent team made every effort to keep bolting to a minimum. Spying out a line of subtle features and drilling a few bolts to fill in the blanks, they were able to weave a magnificent line up this huge chunk of rock… the route quickly became a renowned test of trad climbing skills, and for a few years was climbed regularly. It now receives fewer ascents in a year than Prince of Darkness gets on an average day.”

– Jerry Handren (Description in Red Rocks: A Climber’s Guide)

Shortly after Risky Business, the Alpine Peanut and I were relocated to Southern California for work. We spent the next three months honing runout tolerance in Idyllwild and Joshua Tree, lands of smooth granite, delicate footwork, and sparse bolting. To build fingers capable of clinging to vertical pencils long enough to fiddle with tiny gear, I hangboarded weekly. To build endurance I trained pull-ups, and bouldered aggressively both inside and out. Lastly, I visualized the route. Visualization has become an important preparation element for my hardest projects, even if I’ve never physically seen them. From the scant Rock Warrior internet information available I conjured a mental replica, climbing it regularly during my evening shower. I imagined how petrifying the 60 foot free solo to the first bolt would be. I imagined the jarring sensation of 5.10 edging mixed with nuanced route finding high above a nest of marginal wires. I imagined the unnerving exhaustion and pressure cocktail of cranking a 5.10 roof on the very last pitch, 800 feet off the ground. I imagined the electrifying feeling of clipping the final anchor, as well as the terror of ripping gear and careening 100 feet down the wall. I believe visualizing the worst possible outcome is important too. That way, when those inevitable fears arise on the wall, I’ve already dealt with them. No surprises was my motto.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

Bobbi and I’s Southern California work season wrapped up October 23rd. With Rock Warrior the sole point of focus, and inspirations for other long multi-pitch adventures, we planned a two week Vegas stint for early November. We spent the week prior in Joshua Tree, where I put the finishing touches on my Rock Warrior progression by climbing two scary dream routes: Stick To What (5.10a R) and Run For Your Life (5.10b R). The former has a very high second bolt, requiring a sustained section of 5.8/5.9 friction with surefire 30 foot groundfall consequence, an apt simulator for the opening solo of Rock Warrior. The latter was especially meaningful, considered a top contender for best Joshua Tree face climb of any grade, with long falls possible on 90 feet of abstruse, steep and insecure 5.10 climbing (cough cough… sandbag!). When I told my best friend, climbing partner and mentor Chris Hackbarth, who has climbed both Run For Your Life and Rock Warrior, he responded: “there’s no move even close to as hard as Run For Your Life on Rock Warrior.” My conviction was cemented. I was ready.

On November 8th Bobbi and I trekked into Black Velvet Canyon, joined by Idaho friend Joy Seward. Our original plan was to climb the four-star classic Dream Of Wild Turkeys, saving Rock Warrior for another day, but November is prime Red Rocks season. As we left the car I reflexively grabbed the already racked ballnuts, RP’s and micro-cams. If there was one Black Velvet route that wouldn’t have a line, it would be Rock Warrior. Sure enough, there were two parties on Wild Turkeys and another two in queue. The brilliant black buttress of Rock Warrior and Sandstone Samurai laid seductively dormant. Thirty minutes later I was tied in for the dream, craning outward to find the camouflaged first bolt 60 feet off the ground. None of us spotted it. Just as my visualization predicted, Rock Warrior would require ample amounts of intuition and blind faith. I started up.

A sixty foot apron of rounded, slabby and soft Navajo Sandstone, not dissimilar to the Eastern Plateau of Zion, defends the varnished Rock Warrior headwall. The climbing began gentle, low-fifth class scrambling on generous features, but steadily thinned and steepened approaching the varnish. Once mindless jugs were replaced with bald scoops and imaginary handholds. An obvious rightward traverse of increasing smoothness led to a lonely bolt miles away. Reaching the clipping stance demanded a half dozen paddles of pure 5.7 friction. “Breathe, trust your feet, heels down, one move at a time…” I whispered to myself as I cautiously weighted the edgeless smears. With the first bolt clipped I gazed longingly upward into a disorienting maze of black plates with no obvious path. I could see the anchor almost 100 feet above, but not the second bolt. Following a rare trail of chalk which would disappear entering the second pitch, I crept onto the main wall, finding two solid offset wires in 30 feet before blanking out in the first obvious crux. I fiddled a bodyweight brass stopper into a sandy flare, which promptly popped as I moved right to a prominent leaning flake. A strenuous 5.10 layback and mantle onto the flake fully committed me to Rock Warrior. Down climbing was no longer an option. With help from a belayer on the nearby second pitch of Wild Turkeys I spied the second bolt still 20 feet above, placed in a shallow right facing recess. I was instantaneously petrified and actualized, for this was exactly the experience I sought from Rock Warrior. A lengthy sequence of irreversible crimping and high-stepping with heinous ledge fall potential brought me to the second bolt, after which the climbing became slightly harder but much better protected. A thin and technical tips seam swallowed just about every micro-cam and RP on my anemic rack, culminating in a punchy throw to a chalked pocket and the first of many hanging belays. Power screaming, combined with the obvious reality I was not on the popular Prince Of Darkness bolt ladder, garnered attention from other parties. As I clipped the anchor and transitioned to belay, a silverbacked Red Rocks veteran on nearby Refried Brains (5.9) shouted out: “nice work, Rock Warrior.”

Lore denounces Rock Warrior’s first pitch the “psychological crux” and most dangerous on the route. Though both graded 5.10b, the second pitch is considered the “physical crux”, with more sustained difficulties, but on a steeper wall with better protection. I corroborate this statement. A leftward traverse directly off the belay led to two well spaced bolts and a long podded finger crack on the only overhanging pane of the wall. Wild bouldery climbing on reachy finger locks protected by rusty pitons and shallow gear tested my finger strength, especially when locking off to fuss with protection. Just as the drawing pump became relevant, an unquestionably solid #0.5 Camalot, the largest piece I would place on the entire route, provided full confidence to quiet the mind, commit fully, and punch it to the belay. I power screamed through the final moves and mantled into another tenuous stance. While bringing up the ladies, I realized I missed a third protection bolt on the upper half of this pitch, providing a hypothesis for why the climbing felt substantially harder than the 5.10c crux pitch of Risky Business. As brushed on earlier, staying on route, while also having enough physical and mental margin to wander off route, are equally important on these arcane outings.

The third pitch was much of the same, 150 feet of runout, steep and technical 5.10a face climbing connecting two vague seems, protected by two bolts, a piton or two, and solid but inconsistent small gear. A thin smear and long reach over a small white rock roof with especially poor protection was the crux. Above pitch three the wall angle wanes significantly. Unfortunately, so does the protection and rock quality. Pitch four was a playful and beautiful 5.9 jug haul on creaky sandstone flakes, protected by a lone three bolts in 150 feet with no trustworthy supplementary gear. A delicate touch, three points of contact, and vigilant rock assessment was paramount, with possible falls nearing 100 feet. Pitch five twisted through an especially memorable band of smooth varnish, with a higher degree of technical footwork than the previous four pitches – another winding dance with three bolts and the occasional bongo flake for a low percentage ballnut. The belay was defended by a heartbreaker 5.9 mantle 30 feet out from the last bolt – “breathe deep, step high, core tension, heels down, stand tall, clip the chains.” Facing impending darkness we switched to fixing and following above pitch four. Joy bravely and proficiently learned to top-rope solo 600 feet off the ground. Bobbi followed quickly with an emphasis on pace. We had 30 minutes until nightfall to finish the last 5.10 pitch – everything was clicking. A penultimate 5.10a crank over the steepest bulge of the wall gave way to a glorious sprint up low angle jugs and the first stance larger than a fencepost on the entire route, a three foot by ten foot white rock ledge marking the top of the wall. Four rope stretching 70 meter rappels through a golden November sunset and into deep night landed our team of Rock Warriors on terra firma.

My experience on Rock Warrior bordered transcendent, one of those mystical days where preparation, inspiration, rest, weather and partnership fully aligned. Unlike Risky Business, Run For Your Life, or any of the other dozens of trad climbs I’ve wagered my biscuits on, I was never truly scared. In the dangerous moments I was suspiciously calm and focused. The confounding matrix of Black Velvet edges, ripples, cracks, side-pulls and long reaches made sense. I didn’t waste energy placing questionable protection, instead using my physical ability and prior experience as protection until an obvious gear placement appeared. After pitch three the climb took a playful course. The extremely runout 5.9 pitches felt like surfing a mile long break. My body swam through the stone fluidly and unconsciously, swinging from jug to jug, dancing from smear to edge, all while I intentionally looked down to revel in the craning exposure I came to Rock Warrior for. Cresting the final 5.10a roof brought an elevated wave of emotion I seldom feel anywhere in life, let alone climbing. The warming support of Bobbi and Joy was palpable. Both flashed every pitch with acute attention to our short mid-November daylight window. Managing two ropes and three humans at five straight hanging belays isn’t easy, but we made it work. In the hardest sections of climbing they kept a calm demeanor, never deterring my focus. At risk of sounding cliche, Rock Warrior really felt like a team accomplishment.

I’m still glowing from Rock Warrior, and reckon I’ll be for weeks, months and years to come. The layman often thinks runout routes are for adrenaline junkies with inflated egos and something to prove. However, that’s certainly not my case. Instead, Rock Warrior transports climbers backwards in time, to an era where adventure and self exploration were embraced as an inherent component of climbing. If Rock Warrior had 12-16 bolts per pitch like Prince Of Darkness, it would be just another Mountain Project tick. If you the scan the comment section for Prince Of Darkness, this phenomena is confirmed. People use words like boring, repetitive, painful and monotonous to describe the route, which climbs through the exact same wall with near identical holds to Rock Warrior. As George Bell, a climber from Colorado, wrote on Prince of Darkness’s Mountain Project page: “You don’t hear anybody complaining that Rock Warrior is monotonous or painful! I guess when you’re led out 30 feet that’s the least of your worries. Just goes to show that less frequent pro can make for a totally different climb.”

Perhaps therein lies the real secret sauce of traditional climbing, what the Adventure Punks have tried to preserve through routes like Risky Business, Rock Warrior and Sandstone Samurai. Such undertakings require more than mojo and muscles. As another commented, “Rock Warrior is a route for those seeking out a journey.” For me, that journey was a masterclass in the sprawling return of obsession, preparation and commitment. I derive incredible satisfaction from breaking a seemingly impossible puzzle into digestible pieces, working tirelessly at each piece, and putting the now attainable puzzle back together. Almost all my most meaningful mountain experiences fit this framework. For me, the physical challenge of the mountains is a disproportionately small slice of the pie. I climb and ski to build powerful relationships with myself and partners, experience dynamic and enlivening natural environments, and grow as a human being. Rock Warrior checked all three of those boxes.

To conclude on a less existential note, scampering up such a steep and blank 800 foot wall with only a dozen bolts, slim rack and nothing larger than a #0.5 Camalot is an experience unfit for words, encapsulating everything I love about traditional rock climbing. On the night of November 9th I slept especially sound, proud to have earned the coveted badge of Rock Warrior.

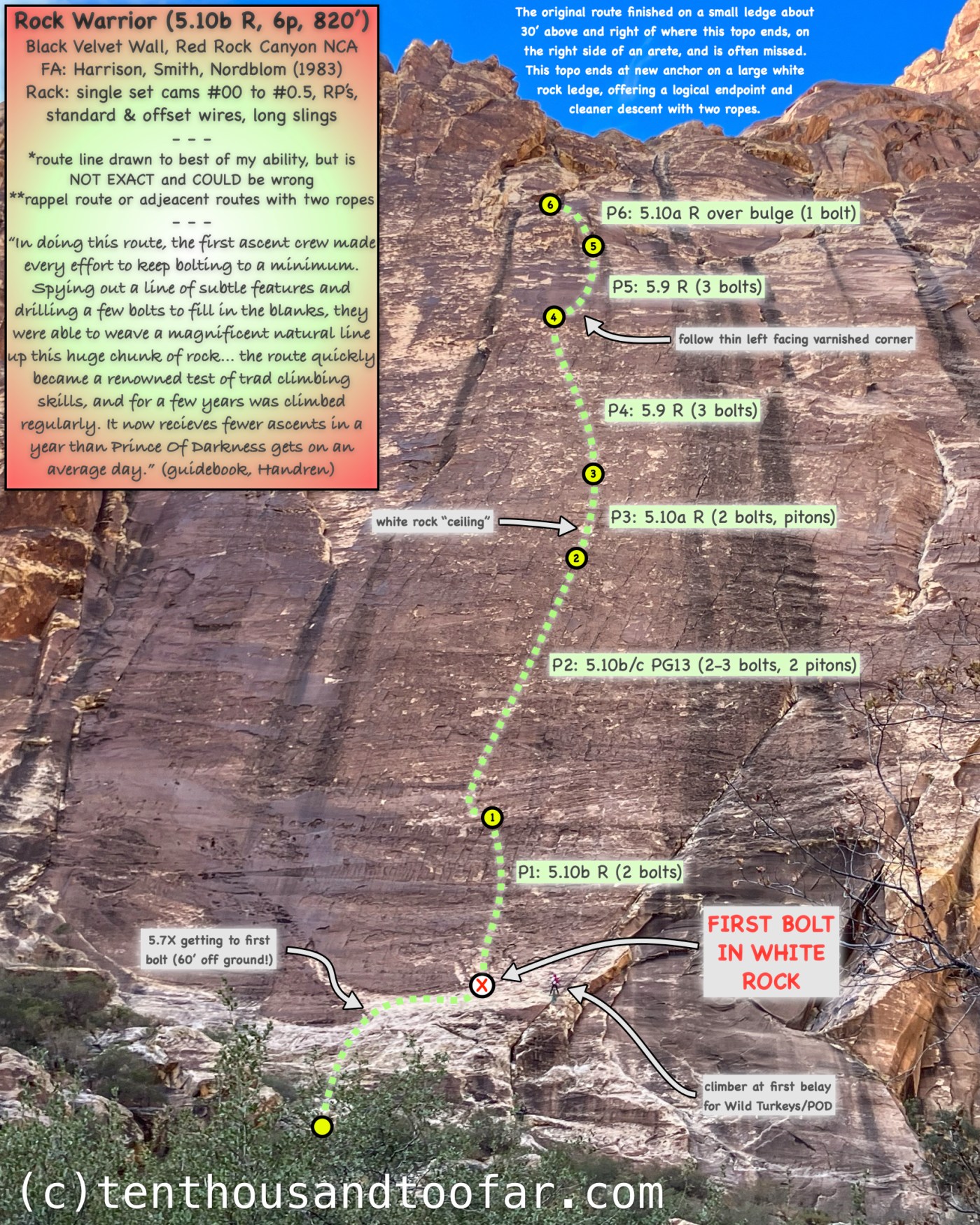

For climbers interested in Rock Warrior, a pitch by pitch route description is included below to supplement the above topo.

Rock Warrior (5.10b R, 6 pitches, 800′) – Route Description

Approach: Rock Warrior is located in Black Velvet Canyon on the Black Velvet Wall, just left of Dream of Wild Turkeys and Prince Of Darkness, two of Red Rock’s premier routes. Between guidebooks and the internet, you’ll find this wall. Budget an hour for the approach. The route begins in unappealingly dirty white sandstone, further left from the first bolt than you’d think. After a short steep section getting off the ground, the terrain above should look very easy.

Pitch One (5.10b R, 150′): The psychological crux. Scramble up easy, albeit occasionally gritty, white Navajo Sandstone until a logical traverse right reveals itself. Friction horizontally across unnervingly bald dishes to the first bolt (5.7 X), located in white rock just before the steep varnish, about ten feet left of the first pitch bolted anchor for Prince Of Darkness and Wild Turkeys. This bolt is 60 feet off the ground, and if you’re lucky enough to find gear beforehand it will be of dubious quality in soft rock, and very far away from the hardest slab moves. The pitch one anchors can be seen 90 feet overhead from this bolt, but the second bolt cannot. Continue upward and gently right with intermittent protection to the second bolt in a shallow recess, and follow a thin seam to a hanging belay (5.10b R).

Pitch Two (5.10b/c PG13, 140′): The physical crux – better protected than pitch one, but significantly steeper and more sustained. Face climb left and up to a bolt, then run it out to another bolt (both bolts can be seen from the belay). Difficult moves past this bolt lead to an angling overhanging finger crack with a few fixed pitons and reasonable protection, fizzling out just before another hanging belay. The first ascent party may have climbed right of this crack and placed another bolt on this pitch, a bolt I did not notice until looking back from the belay. The Handren guidebook and Mountain Project disagree often. Regardless of path, this whole pitch is solid and sustained at the 5.10 grade.

Pitch Three (5.10a R, 120′): Climb up and slightly left to a bolt, and shortly after an aging piton. Boulder over a thin overlap in white rock (5.10a R), then proceed right on easier terrain following different crack systems, passing another bolt and maybe a piton, to another hanging belay. The Handren guidebook calls the overlap a “white rock ceiling”, but that is misleading. In reality, it’s a six inch square cut overlap.

Pitch Four (5.9 R, 150′): The hard climbing and wall angle relents, but the runouts ramp up. Punch it 150 feet through a dizzying maze of playful, albeit precarious and creaky, sandstone flakes. Expect little worthwhile protection besides three bolts roughly 40 feet apart. Each bolt can be seen from the previous with a discerning eye. Belay on a tiny sloping foot ledge, from an anchor in dense chocolate rock.

Pitch Five (5.9 R, 130′): A change in style from the previous four pitches, with an emphasis on thin slab technique and route finding, and less mindless cranking. The runouts remain, but by now you’re immune to fear. Move right off the belay, clipping an immediate bolt to protect against a factor two, then run it out 50 feet up a beautiful varnished slab to a savior bolt, weaving in and out of a subtle left facing corner. Clip another bolt or two in this extremely runout 130 foot pitch. The occasional bongo flake is available for comically desperate protection.

Pitch Six (5.10a R, 130′): Short and sweet. Climb up to an obvious bolt on an overhanging bulge, left of a prominent corner. Boulder over the bulge, don’t choke and break your ankles, and enjoy glorious jug hauling to a large white rock ledge, the first ledge bigger than a baseball bat in 800 feet. From here you have three options:

Option One: For whatever reason the first ascent team bypassed this huge ledge and continued 20-30 feet up the varnished slab above, placing an anchor on the right side of the arete you just bouldered over. This anchor is located on a small ledge invisible from the white rock ledge, is notoriously difficult to find, and has been missed by many.

Option Two: Alternatively, a new anchor not depicted in the Handren guidebook has sprouted on the leftmost edge of the large white rock ledge, offering a logical endpoint and direct linear rappel descent to the pitch four anchors with two ropes. This anchor is not a part of Sandstone Samurai, which ends 20 feet below and well left, in a black water stream. I can only imagine it was added to streamline the descent.

Option Three: Continue to the top of Black Velvet Peak with several more adventurous pitches in the 5.8/5.9 range and no more fixed anchors. The original route ends at pitch six. Most parties rappel.

Descent: If you continued to the original anchor for pitch six, the best rappel descent may be down the cleaner wall of Prince Of Darkness, or to the pitch five belay. Attempting to rappel around the arete to the pitch four belay with two ropes would likely get a rope snagged or dislodge the loose rock on the aforementioned white rock ledge. If using the new anchor on the white rock ledge, four 70 meter rappels will get you to the ground via the pitch four belay, pitch two belay, and Prince of Darkness/Wild Turkeys pitch one belay. Rock Warrior has reportedly been rappelled anchor to anchor with an 80 meter rope. There are many anchors for nearby routes on this wall, including Prince of Darkness to the west, and Sandstone Samurai to the east. There’s probably two dozen different ways to rappel this wall with different length ropes, but having two ropes will increase your options.

Bonus Beta: Prince of Darkness is the next route right of Rock Warrior. With a shiny bolt every body length, a dead vertical climbing line, and as much chalk as sport classics in the Black Corridor, it forms a very obvious western boundary for Rock Warrior.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Range Meal Bars, The High Route, Black Diamond Equipment and Barrels & Bins Natural Market.

subscribe for new article updates – no junk ever

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.