In 2015, David Gonzales wrote a popular article for POWDER Magazine titled “Is There A Better Way to Ski the Grand Teton?” – in which he discusses the perilous and increasingly pressing issue of congestion on the Grand Teton’s most popular ski route, the Ford-Stettner. This article will double down on Gonzales’s work, putting a microscope to the Workman-Starr Sneak and it’s potential to reduce overhead hazard when multiple climbers/skiers are on the mountain.

What’s the Problem?

Once upon a time, skiing the Grand Teton was a monumental feat of alpinism. Gradually, much like all things mountain sports, the extreme feat of starting well before dawn to climb 7,000 vertical feet of mountain, including several hundred feet of highly exposed water ice at 12,000 feet, and skiing 50 degree “no fall” terrain above life ending cliffs while criminally sleep deprived, has become almost normalized. I say almost because skiing the Grand is still a big deal, just not like it was two decades ago when maybe only a dozen or so crazy beasts graced the the 13,775 foot monster each winter. Nowadays I’d reckon the big stone sees well over 100 parties per winter season, and of those several hundred descents, 98% occur on the Ford-Stettner route. Why is this a problem? Well, without diving into unnecessary minutia, the Ford-Stettner is composed of three independent couloirs – Ford, Chevy and Stettner – which conveniently flow into one another like a network of PVC plumbing. As such, any dislodged chunk of rock, ice or snow, dropped gear, rag-dolling human or god forbidden avalanche, released at any point in the Ford-Stettner matrix, is headed for ground zero, whizzing past – or into – all following climbers. Honestly, it’s a miracle the Grand Teton has never seen a winter fatality in the modern ski-mountaineering era. An average party on the Ford-Stettner will take a few hours climbing through several pitches of ice in the Stettner and Chevy Couloirs, another hour or three climbing and skiing the Ford, and another hour or two rappelling upwards of five times right back through the Chevy and Stettner. Essentially, this article can be boiled down to one main goal: how to realistically minimize time spent in the Teton’s deadliest bowling alley.

But Aren’t There Other Routes?

Instead of delving into the multitude of other Grand Teton ski routes, including but not limited to the Owen-Spalding, Briggs Route and Otterbody Snowfield, this article will focus on one slight variation to the Ford-Stettner that could alleviate much of the overhead danger when multiple parties are on route, the Workman-Starr Sneak. Compared to the half dozen other congestion relieving strategies the POWDER article offered, the Workman-Starr is by far the most practical, requiring no less skill or knowledge of the mountain than is otherwise needed to ski the traditional Ford-Stettner. “Almost every time I see someone climbing the Grand, I ask them if they know about the Workman-Starr” said one of EXUM’s head mountain guides. “I probably ski it more often than the Ford nowadays too.” Alright – let’s get into it – so what exactly is the Workman-Starr?

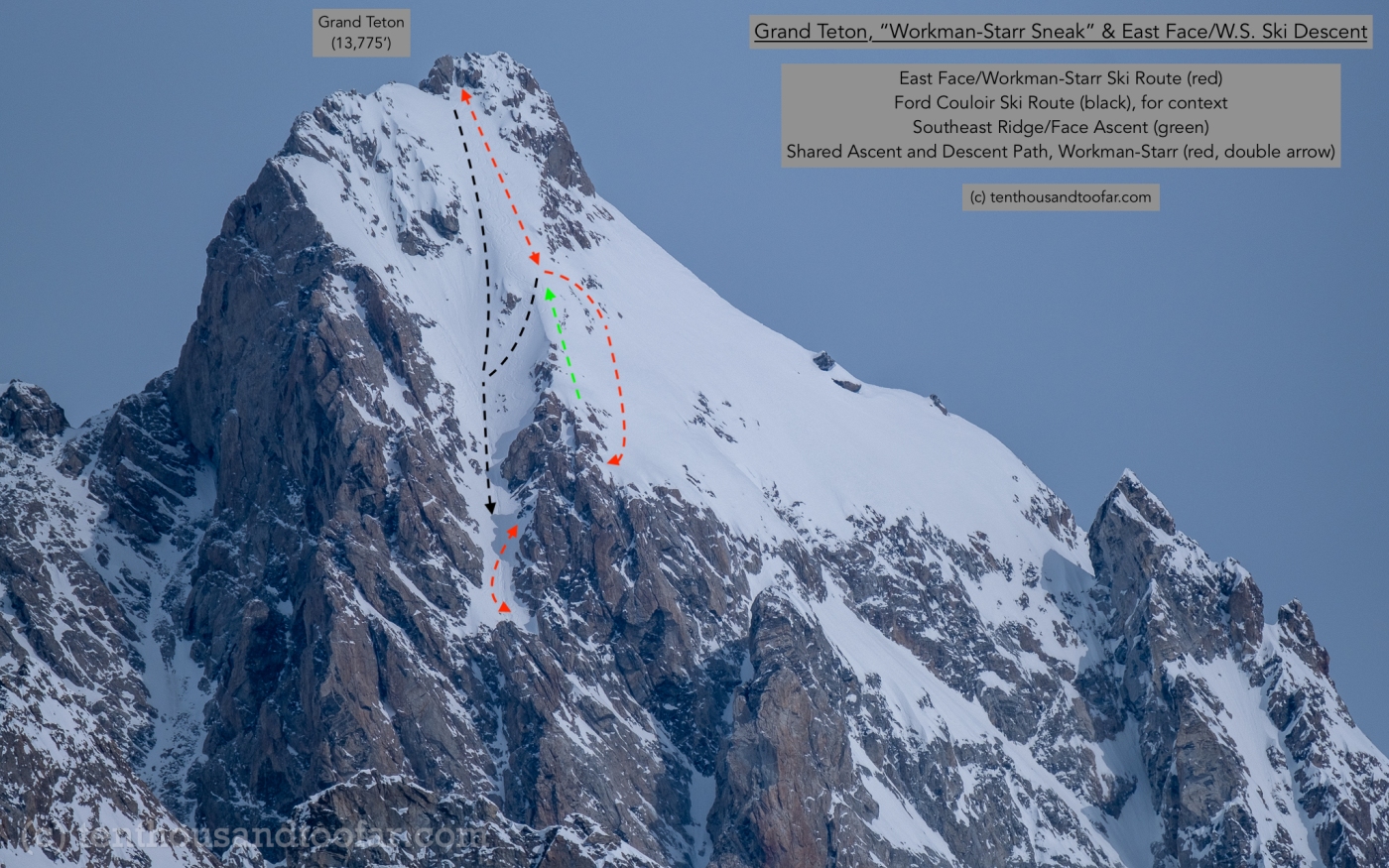

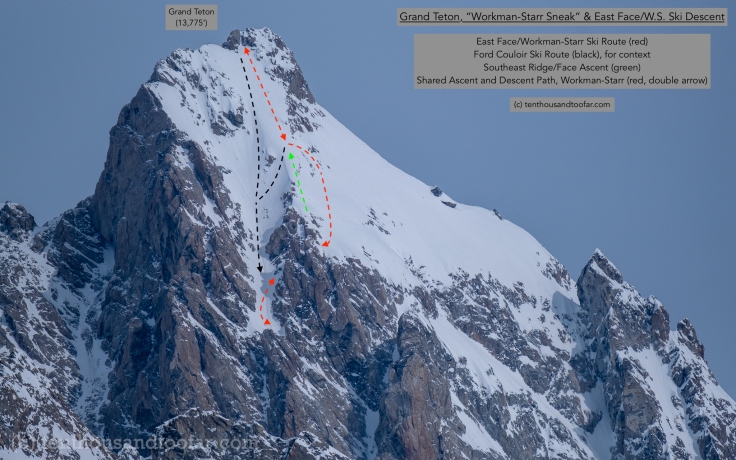

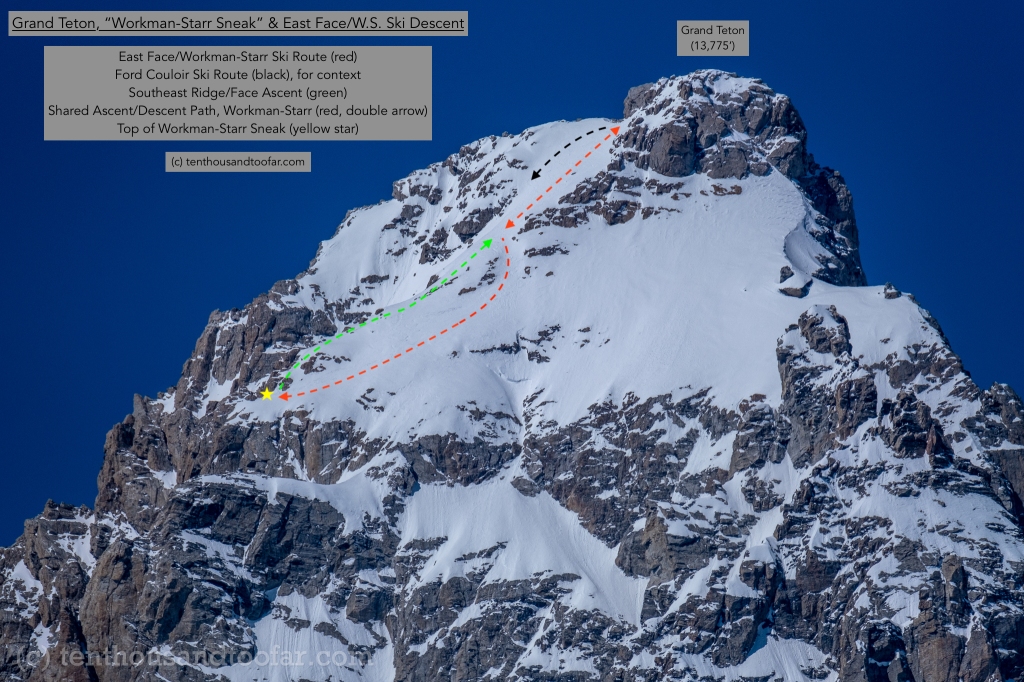

The Workman-Starr Sneak

This isn’t a “how to ski the Grand Teton” article, so we’ll start off at the base of the Ford Couloir. One has just finished several hundred feet of ice climbing and romped to the rappel station at the west side of the Petzoldt Col. Hopefully they started early and are ahead of schedule – i.e. the mountain is still frozen. They stare up the massive Ford Couloir, but instead of just punching up the gut, a weakness reveals itself to climber’s right – the Workman-Starr Sneak – a steep snow chute trending east, from the Ford to the Southeast Ridge/East Face. 100-200 feet of the Ford must be climbed until this line is fully visible, and I’ve heard it can be a little rocky but easily navigated in low snow. A boot-pack directly up the Workman-Starr, perhaps 50 degrees, leads to the ridge. Above this, a mellow, non-technical and unbelievably scenic climb of the Southeast Ridge and Face leads to the summit block. Bingo! But why take the trouble to reinvent the wheel, when one could just climb the Ford?

The Showdown – Ford Couloir VS. Workman-Starr

Ascending the Workman-Starr has many advantages over the Ford Couloir:

- Debris shed while climbing the Southeast Ridge will fall down the East Face, not endangering ascending parties

- Debris naturally shed on the upper mountain will not hit ascending parties

- Ridges are preferable avalanche slopes to couloirs

- Ridges often hold more consolidated snow for more reliable ascents

- The Southeast Ridge has better views

- The Southeast Ridge receives sunlight earlier, nice for parties climbing in colder weather

The only drawbacks to climbing the Workman-Starr would be navigating rocky terrain early season, and an inability to “assess” the Ford as one climbs. That said, usually parties skiing the Grand Teton have a pretty locked idea of conditions, so the latter shouldn’t be much of a deterrent.

As a ski descent, the East Face/Workman-Starr also has some advantages over the Ford:

- Skier debris will shed down the East Face, not endangering parties below

- Earlier sun exposure means earlier “soft” conditions, allowing for earlier spring descents

- 50 degree jump turns on the wildly exposed East Face of the Grand Teton rival any ski descent in North America – redefining the word “aesthetic”

As a ski descent the East Face/Workman-Starr does have some drawbacks compared to the Ford:

- Less “fall line” of a descent

- More difficult route finding (knowledge of terrain, following ascent tracks and staying close to the ridge is preferable)

- Major exposure to East Face cliffs (though the Ford has significant exposure and steepness as well)

- The Sneak is often too thin or frozen (or both) to be skied, requiring a small bought of side slipping or down-climbing

- And yes, I know – the Workman-Starr is not featured in the 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America, for all the Cody Townsend’s out there

Summary, Alternate Routes and a Few Notes on Rappelling

Even if one chooses not to ski the Workman-Starr, there aren’t many good reasons not to climb it. In my opinion, it should be the standard winter ascent. Ridges naturally have less exposure to overhead debris and avalanche hazard, usually harbor more consolidated snow and are standard routes for ascent on the majority of large mountains across the globe for that very reason. I can understand wanting to ski the “50 Classic Ski Descent” Ford Couloir, with one thousand feet of mega exposed, fall-line shred on the tallest peak of Teton Range – yep, it’s awesome. But when several parties are climbing technical water ice in the Chevy and Stettner below, camped in the firing lane for each and every wash of slough, snow and ice your skis kick down, there is an humanitarian argument to be made for skiing a different route. Furthermore, the East Face/Workman Starr descent isn’t exactly chump change. If anything the turns are more airy, aesthetic and wild than the Ford. Also, because of the East Face’s obvious easterly aspect, it receives sun and warming before the Ford, meaning if one is “early to the party” on a well frozen Grand Teton, the variation may be the first and most logical way down the mountain.

As far as alternate routes the POWDER article talked about – I can sympathize. If every GT skier had the ability to descend the Owen-Spalding or Briggs Route, or understood the route-finding logistics of the proposed Wall Street Couloir exit (which involves scrambling to Exum Ridge from the base of the Petzoldt Col, some monkey business on fourth class rock, rappelling to the Wall Street Ledge and returning to Garnet Canyon via the often un-skiable Wall Street Couloir) then sure, congestion on the Grand Teton would be substantially alleviated. But considering the advanced technical nature of these alternatives, I’m not sure any are a realistic solution. The nice thing about the Workman-Starr is it’s ease of understanding and implementation. No extra knowledge of the mountain, or technical competency, is required to use the variation for ascent or descent. Sure, skiing the variation doesn’t solve the problem of rappelling/climbing congestion in the Chevy Couloir (that’s where the Exum Ridge/Wall Street exit would save the day) but for now I believe the Workman-Starr is the best we’ve got – a damn good and easily implemented solution capable of solving over 50% of the problem.

One quick last note on rappelling: Most roped descents begin at the Petzolt Col rap station. The only issue I have with this station is that a double rope rappel lands that party on the south side of the Chevy Couloir, at the common second rap station. Not only is this station awkwardly high on the wall and difficult to be used by multiple team members, but it is highly exposed to snow and ice fall from above. I have been pelted by many chunks of ice and uncomfortably washed by several large skier sloughs while tied off at this station. Instead, a seldom used anchor on the north side of the couloir, right before the east wall of the Ford becomes the Chevy, is a brilliantly protected place to stage ropes for descent. For the party comfortable skiing a little lower in more exposed terrain, or down-climbing said terrain, this station makes great sense for a safer descent.

I hope you enjoyed this article. As always, I would like to give a huge thank you to my supporters, Icelantic Skis and Chasing Paradise. Need some new sticks capable of climbing and skiing anything your wild little mind can imagine? Head on over to icelanticskis.com and check out the Natural 101, my tried and true ski mountaineering katana.

Errors? Typos? Leave a comment below or send an email to bwanthal@gmail.com

If you would like to support Ten Thousand Too Far, consider subscribing below and/or leaving a donation here. The hours spent writing these blogs is fueled solely and happily by passion, but if you use this site to plan or inspire your own epic adventure, consider kicking in. A couple bucks goes a long way in the cold world of adventure blogging. I also love to hear your thoughts, so don’t leave without dropping a comment! Thanks for the love.

Follow along on Instagram at @brandon.wanthal.photography

Enter your email – no monkey business – just new content!

DISCLAIMER

Mountains are dangerous. Skiing them is more dangerous. Can’t we just admire those beautiful peaks from the parking lot? With binoculars and a lime Lacroix? Hmm… Nevertheless, mountain conditions change regularly, and the information in this article is only accurate as it pertains to the titled date. This article is written strictly for informational purposes only. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk!