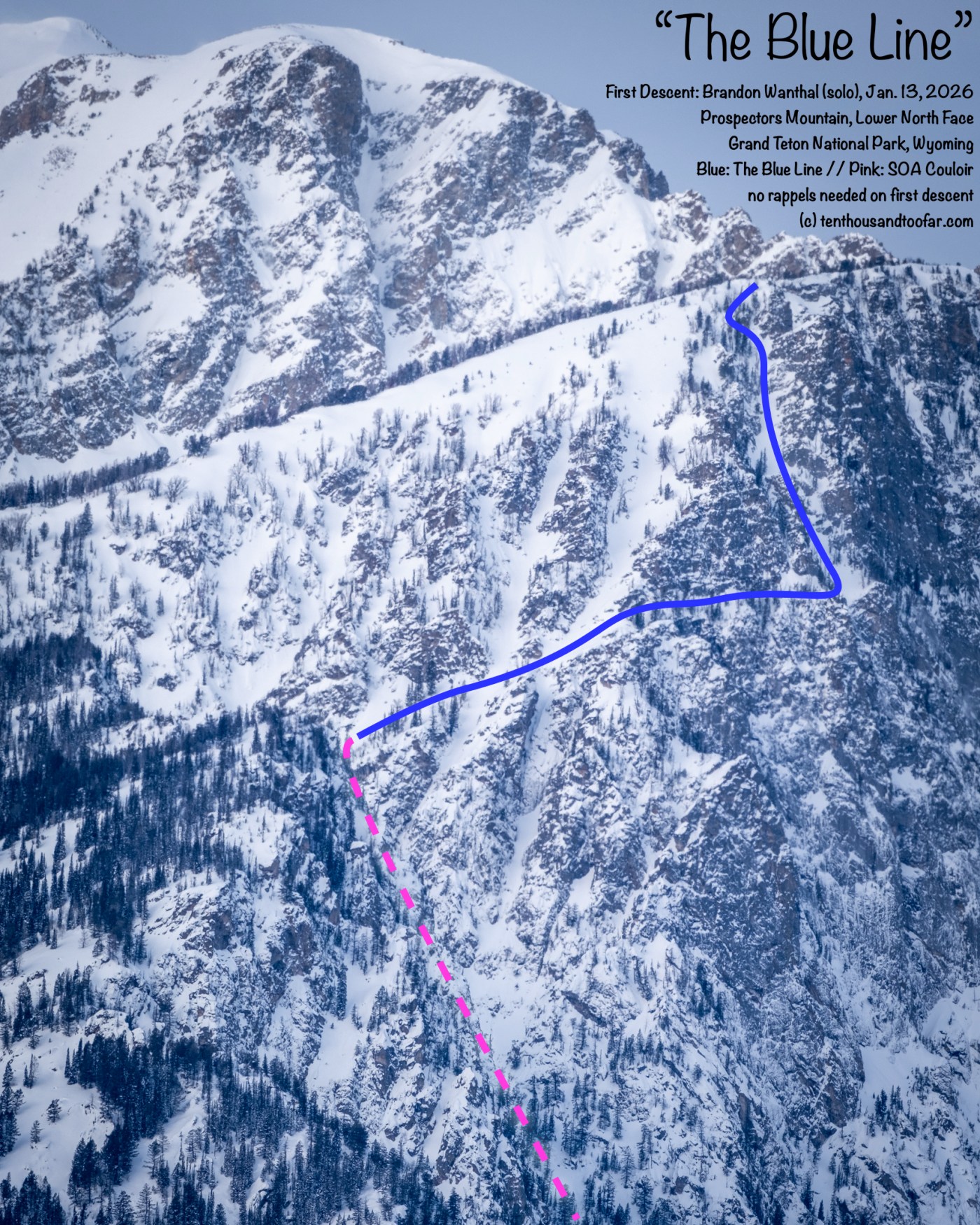

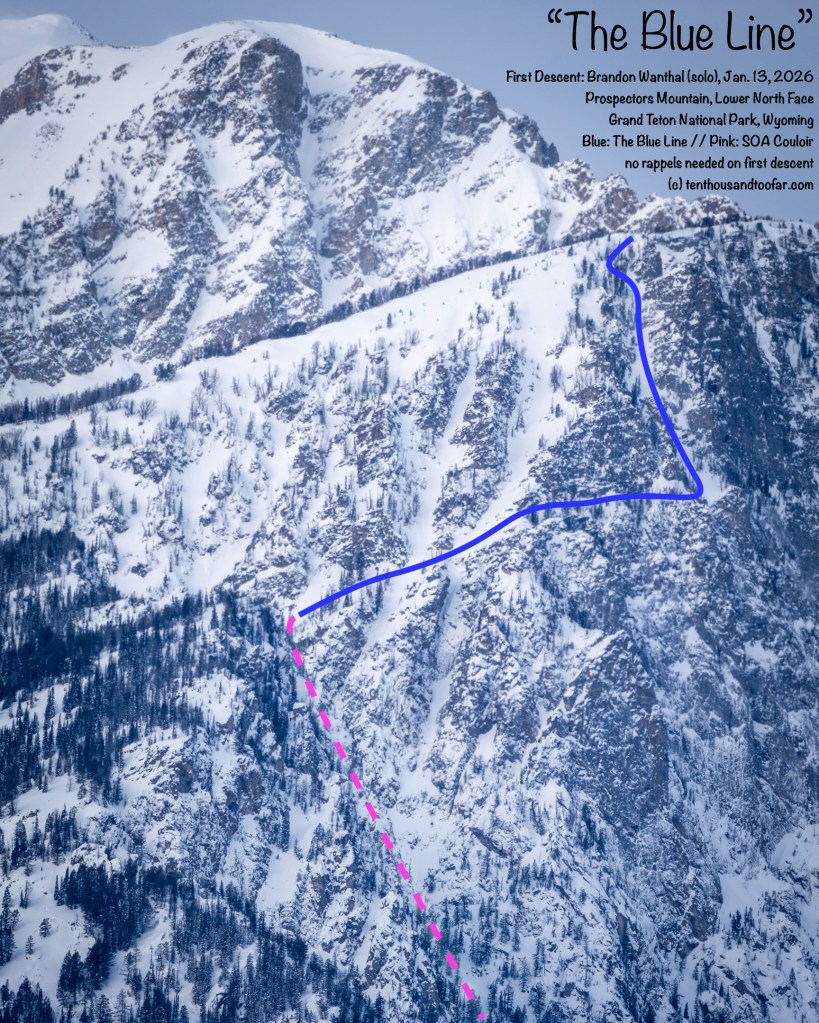

On January 13th, 2026, I completed the first descent of The Blue Line, possibly the last unskied couloir in the Apocalypse area of Prospector’s Mountain. The route features a 700 foot hanging couloir with 50 degree skiing above massive exposure, culminating in a 650 foot horizontal traverse across an unlikely ledge system to merge with the Son of the Apocalypse Couloir, a 3,300 foot descent in full.

Last summer I was corresponding with local guidebook author and Teton ski legend Tom Turiano about rare ski descents in Grand Teton National Park. He sent me a scrappy overlay of the lower north face of Prospector’s Mountain, seeking information about a few fringe descents above, and funneling into, the Son of the Apocalypse Couloir. The furthest west line, what ultimately became The Blue Line, was annotated by a squiggly blue line and the words “no known descents” in parenthesis. At first glance the line seemed desperate, with a massive horizontal traverse above unreasonable exposure exiting a relatively small hanging couloir. No wonder nobody had skied it. But as summer droned on and dreams of upcoming ski season percolated, the aesthetic pull of that faint couloir, combined with the traverse’s extreme improbability, hijacked my imagination. First descents in a range as well explored as the Tetons are exceedingly rare. Last year I accomplished my first “first descent” with the North Face of Wanda Pinnacle (a.k.a. Air Traffic Control). The experience was exhilarating. Skiing down uncharted terrain, where no human has passed before, serves an adventure quotient unfit for words. I’d done a handful of first linkups, first solo descents, second descents and rare descents across the range with no beta, a reasonable proxy for a first descent, but not quite the same. Whilst skiing down Wanda I feared ambush at every turn. Would there be reasonable rock for an anchor? How steep and exposed would the final turns to the edge be? Will my rope reach? Is there some part of the puzzle I was missing? Technical first descents feel like a finals exam – a test in spontaneity – the ability to solve every possible ski mountaineering problem swiftly while faced with the gravest consequences. Having dedicated ten years of my life to ski mountaineering in the Teton Range, envisioning new ways to move through these mountains feels like a right of passage.

As the first heavy winter storm cycle of 2026 waned into high pressure, I was impressed with the snowpack and circled back to the mysterious blue line on Tom’s topo. Logically I should have waited until March – the line appears bony as all hell and sits at relatively low elevation – but the nature of Bobbi and I’s new career in desert biology dictates that we could be called back to the Mojave at any moment, effectively ending ski season. I was craving another Wanda-esque experience. Furthermore, I have a short list of other new lines – of greater complexity in higher places – I hope to attempt this year. I thought The Blue Line a proper way to calibrate my readiness for the ski mountaineering season ahead.

On January 13th I headed into Grand Teton National Park far after dawn with my mirrorless camera and 400mm zoom lens. I photographed the line from the parking lot to assess my two biggest questions: would there be a rappel in the upper couloir, and would the 650 foot hanging traverse be quasi-sane. When you examine The Blue Line on Caltopo or OnX, gauging feasibility is difficult. In person I was surprised to see a natural line that appeared to ski cleanly without a rope, and an uninterrupted all-snow traverse. I gained the ~10,180′ summit pinnacle spanning the Son of the Apocalypse and standard Apocalypse areas three hours after leaving the car. Another damned inversion held temperatures above freezing at 10,000 feet, but strong and bitter winds kept snow surfaces cool as a cucumber. A thick veil of trees atop a rugged cliff blocked clean views of the couloir from above. Even with GPS confirmation I was in the right place, I struggled to suppress an eerie feeling that I could somehow, someway, be dropping into the wrong line. I wiggled into the couloir via a steep traverse from the eastern ridge over stiff windboarded snow. Until this point my gut was rife with butterflies I rarely feel with skis on my feet. But when I reached the gut of the upper couloir, greeted by perfect settled powder and a clean fall-line chute, the nervousness vanished. “Oh, I can do this”, I spoke to myself out loud.

The upper couloir was truly spectacular. The initial pitch involved sustained 50 degree skiing funnelling into a rollover and a ski-width crux. My jump turns, untested since last May, felt clean and precise. The crux was even tighter than I imagined, scraping both tips and tails of my 185 centimeter skis. A brief dry rock slab required some “dry skiing” tactics, but below was a mellowing belly of carefree 45 degree powder on the edge of the universe. Every turn sent dry snow cascading over the omnipresent 1,500 foot cliff below. Fortunately, both snow stability and conditions were on my side. In full, it was 700 feet of the better steep skiing I’ve enjoyed in my life. Nearing the edge I spied the obvious exit to the eastward traverse ramp. I was surprised to find more horizontal downward pitch on this ramp than expected, but also a steeper direct slope angle towards the cliff. 650 feet of gravity assisted shuffling above the ether, on snow as steep as 50 degrees, saw me to a final unexpected crux – a body height cornice barring exit to a flat notch marking the conclusion of uncharted territory. This cornice was stiff and stubborn, perched all of 20 feet above the cliff edge. In order to keep skis on I carefully dismembered the obstacle with my ski tips and poles. I broke off chunks the size of basketballs that bounced down the north face of Prospector’s Mountain like a haul bag cut from El Capitan. But soon enough, I slipped over the beast and into salvation.

From this notch I followed a lightly cambered and angled bench to the Son of the Apocalypse Couloir, grinning from ear to ear despite a now heinous breakable crust. The couloir itself was entirely wind gutted, but skied surprisingly well with one light inch of dust on an otherwise soft but supportable crust. A surprise 20 foot nugget of seasonal water ice blocked clean exit just below the apron, which I down-climbed instead of flaking a 65 meter rope for a microscopic rappel off a suspect fixed v-thread. This was the only time I removed skis on the entire descent 3,300 foot descent. Ripping resort style edge-to-edge turns down smooth windboard into the annals of Death Canyon is an experience I won’t soon forget. The Blue Line was complete.

Rather than invent yet another predictable spin on the “Apocalypse” theme of this area, I chose to name the route The Blue Line. Why? Because that’s the exact name I referred to the route as with my partner over the past few weeks. The ambiguity such a name speaks to the mystique of this strange and atypical ski descent. While packing my bag the night before, I feared the 650 foot exit traverse would make the entire adventure feel contrived. Much to my satisfaction, it was exactly the opposite. The traverse is one of the more distinctive places I’ve ever been with a pair of skis on my feet, similar – dare I say – to the feeling of linking turns on the Grand Teton’s mythical Otterbody Snowfield. It may be only 30 feet at the widest, but occasionally I found just enough smooth snow to link a pair of highly memorable turns. The upper couloir offers grandiose exposure over the intense shadowy jaws of Death Canyon below. All in all, The Blue Line is an exciting and worthy ski descent, and possibly the last unskied puzzle that doesn’t require significant rope work on this cliff of extensive Teton history.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Range Meal Bars, The High Route, Black Diamond Equipment and Barrels & Bins Natural Market.

subscribe for new article updates – no junk ever

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.