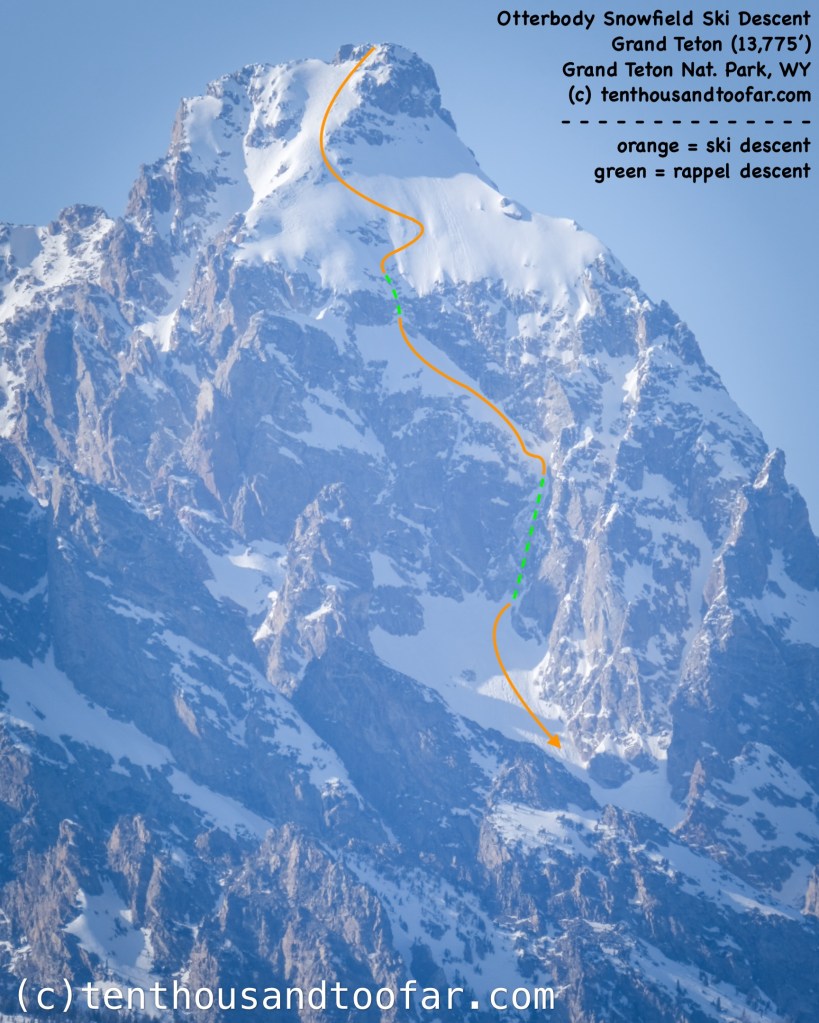

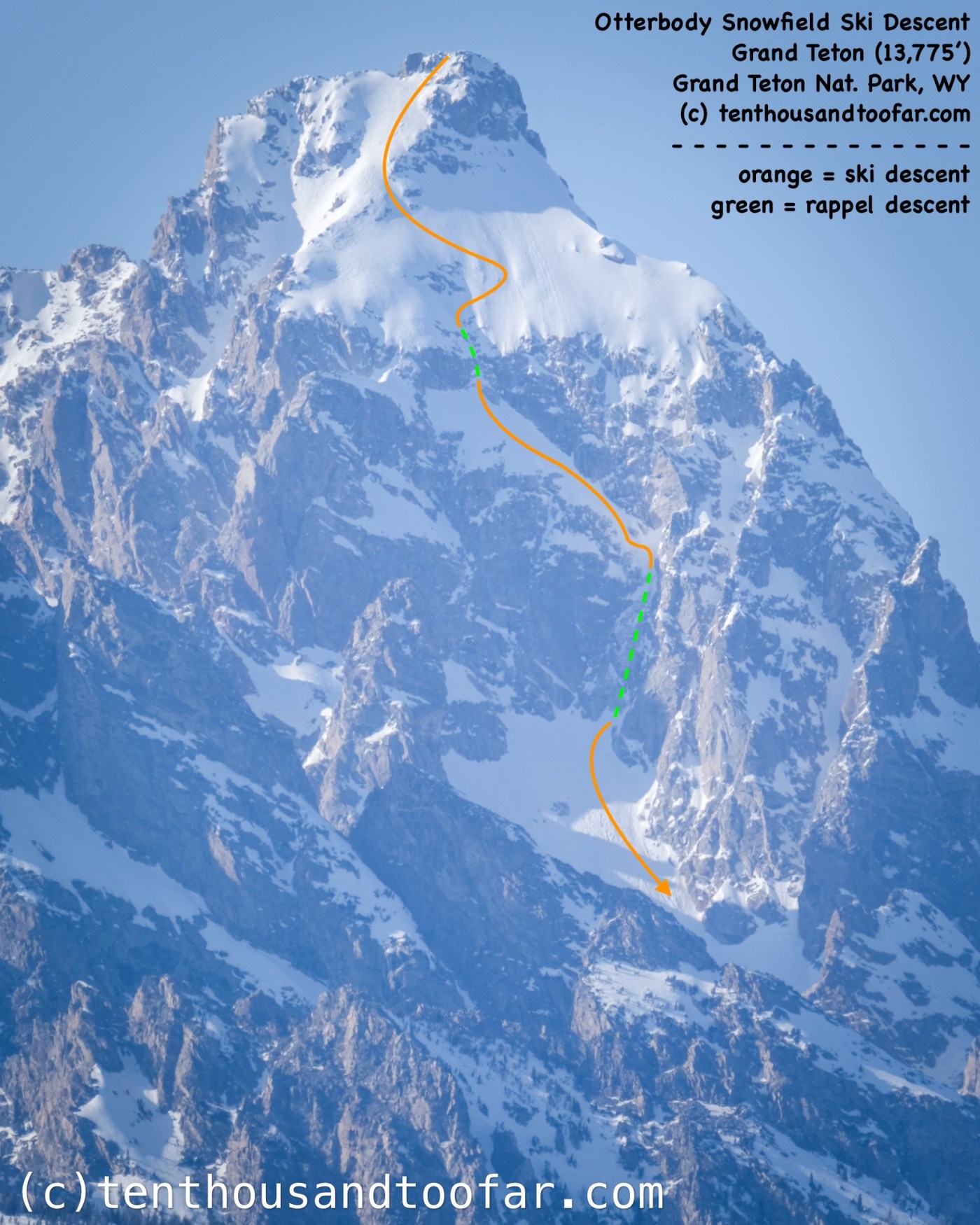

The Otterbody Snowfield is a 1,700 foot fairy tale ski mountaineering descent, 7,000 feet in full, on the East Face of the Grand Teton. On March 30th, 2025, I had the pleasure of descending the route with Hayden Evans and Julian Winston.

It’s hard to put the immensity of the Otterbody into proportion. I’ve skied many a steep line with ropes in the Tetons, but the exposure on this route is different. Skiing onto the hanging East Face of the 13,775 foot Grand Teton is an experience unfit for words. The air beneath my skis was palpable and omnipresent, augmented by the route’s reputation for minimal anchoring opportunities and exfoliating rock. From first turn to last, you’re operating in a true no fall zone with substantial overhead hazard, underpinned by thousands of feet of cliffs. Since its first descent in 1997 by Jackson legends Doug Coombs and Mark Newcomb, the Otterbody Snowfield remains one of the most admired, respected, and feared ski descents in North America. Piecing this incredible natural puzzle together alongside tested partner Hayden Evans, and new friend Julian Winston, represented a significant step in my ski mountaineering journey.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Find the information useful? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

Yes, the skiing itself is ludicrously exposed, complex, and often extremely steep. However, the crux of a successful Otterbody descent is finding optimal conditions. There are three distinct sections of the route: the face, body and tail. The face comprises the first 800 vertical feet of skiing from summit to first rappel, on the gigantic unsupported triangular snowfield visible from hundreds of miles away. The face gets first light at dawn, is generally convex, and contains slopes oscillating from 35-50 degrees. One rappel through a claustrophobic choke, often filled with blue ice and ski-able in only the fattest of conditions, leads to the Otterbody, the angling snowfield below the face named for its loose appearance of an otter. The body is the fattest portion of this snowfield, with a refreshingly gentle slope angle between 40-45 degrees to tame an otherwise otherworldly level of double fall-line exposure. The tail comes last, where the body constricts and steepens to an off-camber sinewy strand funneling into a narrow southeast facing couloir formed by the Second Tower, a massive gendarme of the Grand’s eastern ridge. Depending on conditions, turns can be made down varying amounts of the tail, but the consensus standard for a modern descent in “good style” ends at the precipice of an ice bulge about 400 feet above Tepee Glacier, where three rappels lead to salvation. The tail contains progressively steepening slopes approaching 55 degrees, often haunted by runnels, bulletproof ice and avalanche debris, and is only skied in the finest conditions. On a warming day, the tail is one of the most inhospitable places conceivable. Each year any established rappel anchors are threatened, battered or destroyed by an endless barrage of massive spring avalanches and rock fall. The rock is either compact or extremely chossy, offering limited anchoring opportunities. Furthermore, because of its sheltered location behind the Second Tower, the tail will not see sun until the face above has been baking for hours. Late spring descents (including the first descent) aiming for sun softened conditions are often thwarted when skiers realize the tail will be unskiable until the face above becomes unjustifiably warm. At this point ropes come out, sharps go on, and skiable snow is skipped. As snow science and modern weather forecasting continues to evolve, the optimal window for Otterbody descents has trended earlier. High pressure mid-winter powder offers the possibility of consistent conditions through all three sections, but the thought of skiing such unsupported, steep and exposed snowfields in anything more than a morsel of new snow has always made me nauseous. I aimed to thread the needle between powder and corn – a calm, cold and cloudy day to minimize overhead hazard, and just enough fresh snow for edgeable skiing without avalanche risk. An acclaimed local guide with several Otterbody descents backed this vision. After two years of stalking conditions and refining strategy, the universe aligned on March 30th, 2025.

My partners for the day were long-time friend Hayden Evans, and new partner Julian Winston. I’ve always been adamantly against taking new partners on technical ski missions, but in this rare instance, Hayden’s testimonials from skiing the venerable Northeast Snowfields with Julian, and the allure of carrying less weight on my back to the highest point of the Teton Range, tipped the scales. New to the region, Julian had never climbed the Grand Teton before, but promised fitness, raw ability, and a cool demeanor. Never in a million years did I think I would be introducing myself to a new partner at 2:30AM while driving to Grand Teton National Park to ski one of the most technically demanding descents in North America.

The four days prior to our Otterbody attempt saw the first spring high pressure cycle, with mountain summit temperatures rising above freezing by day, and dropping well below freezing at night. Hours before our departure, a weak pacific system delivered 2-6 inches of moderate density snow with little wind. Single digit overnight temperatures, light winds, intermittent cloud cover, and forecasted highs in the low 20’s for 11,600 feet allowed a “Grand casual” start. We started skiing at 04:00, reached the meadows by 05:45, and Teepee Glacier by 08:30. An abnormal and tricky dry-tooling crux slowed progress in the Chevy Couloir, but we all scratched through without deploying a rope. Persistent shin-depth breakable conditions haunted us through the Ford, Workman/Starr Sneak and Southeast Ridge, delaying our summit until 11:00. Fortunately, the snow was behaving just as we expected. Despite blips of direct sun, surfaces were staying cold for the long haul. Of my six previous Grand Teton ski ascents, this was the first where time was not a precious commodity.

We lingered on the summit for 90 minutes discussing the viability of the Otterbody given the breakable crust of the last 2,500 feet, and bands of thick clouds which intermittently dropped visibility to near-zero. With minimal overnight snow and no warming, avalanches weren’t a primary concern. Instead, our conversations were consumed with fears of navigating both difficult snow conditions and visibility on one of the most exposed faces of our lives. Skiing the Otterbody in breakable crust, or a true whiteout, wasn’t an option. Despite what appeared to be a certain retreat down the nearby Ford Couloir, we racked for the main event and skied to a perch on the Southeast Ridge to assess the face. At 12:30 the clouds broke just enough to expose the first band of cliffs 300 feet below, and with a gang of butterflies percolating through my chest, I departed onto the face. My first turns were cautious hand-checks, anticipating the sickening feeling of plunging skis into breakable crust, but the plunge never came. The crust was somehow… someway… supportable. I gradually eased tension and began linking turns through perfect scratchy March powder, dropping further and further into the void, growing increasingly comfortable with every flick of the hips. Hayden and Julian were genuinely surprised when I reported favorable conditions and called them down.

We ended up skiing the 800 foot face in five short pitches to maintain eyesight and communication, each pitch increasing the commitment, exposure, and reality that we were actually skiing on the mythical East Face of the Grand Teton, linking smooth jump turns at 13,000 feet. Julian later commented that our lack of visibility acted as mental insulation from the 1,000 foot cliff growing closer with every turn, but I had a different reaction. I would have given just about anything for the clouds to lift 1,000 feet. That said, the face has a gentle concavity pushing you towards the crux constriction. Navigation isn’t obvious, but a shake of ski mountaineering “spidey sense”, as well as a recent picture, goes a long way. On the final pitch nearing the edge, skiers are corralled into a convex chute with slopes exceeding 50 degrees, the most exposed position of the entire route. Linking turns here is an experience I will never forget. Furthermore, as the first descent team of 2025 and voluntarily choosing to eschew beta, we had no promise of finding a fixed anchor. One trip report penned a harrowing tale of a single piton anchor in compact rock, and doing a “rope assisted down-climb” to the body. It’s difficult enough to link 50 degree turns within spitting distance of a 1,000 foot cliff when promised a fixed anchor. Without an anchor, it’s the devil’s work – the pinnacle task of technical ski mountaineering. Between every turn I panned the adjacent cliffs for fixed gear, or a crack to build an anchor. The suspense was tangible and building. Millions of years of annual erosion has rendered the very little exposed rock on the face diamond smooth, down sloping, and nearly void of weaknesses. Approaching the edge, the new snow thinned, and the crust beneath less consistent, but to my heart’s delight, an assortment of fixed gear revealed itself. My first instinct was of self preservation – side-slipping to salvation – but my second was different. I hadn’t come to the Otterbody to side-slip, and the snow was still plenty edgeable. I detached from the primal craving of security and continued linking turns to the anchor. The wave of relief I felt when Julian and Hayden reached the anchor safely was transcendent. As we flaked our ropes for the rappel onto the Otterbody itself, the demeanor of our mission shifted. Retreat was no longer an option. The second we rappelled onto the body and pulled our ropes, we would be committed.

True to reputation, the body was benign compared to the face above, allowing us to relish the supreme exposure and ski with fluidity. The snow deepened, presumably due to shedding from the face above, but I wished it hadn’t. Skiing gravity compacted boot deep powder on the Otterbody wasn’t on my agenda, but fortunately matters were well bonded. Wind scoured ribs of dust on crust, and a particularly nasty vein of bulletproof glaze entering the tail, kept us on our toes. Once in the tail, exposure quadruples as the steepest pitch of the entire route reveals itself above a 400 foot sloping cliff capping Tepee Glacier. Linking the final 50 feet of 50-55 degree jump turns to the precipice of the exposed ice bulge, the 2025 ski-able snow-line, was a magical experience tainted only by the dooming fact that somehow… someway… there wasn’t a fixed anchor. And the rock, just as legend told, was exceptionally compact. I carefully unclipped from my skis and slotted them deep into the firm snowpack as an intermediate anchor, switched to crampons, and called the boys down. Watching Hayden and Julian, but especially Julian, negotiate the tail was special. Skiers have an inarguable advantage in firm and steep terrain. Furthermore, I had skied with Hayden plenty – I knew he wouldn’t fall. The bulletproof vein guarding the final ski-able pitch was severe. Julian’s prowess to hold his toe-side edge while gliding across the edge of the universe on his first Grand Teton ski descent was commendable. A misstep anywhere in the tail is a guaranteed and gruesome fatality. Perfection is the only answer.

Manifesting our first anchor took 45 minutes, with all three of us investigating and excavating a 30 foot panel of exposed rock in crampons. Hayden discovered two flakes buried in snow about ten feet apart. The first took two angle pitons and a great wire, and the second another wire. Because we couldn’t guarantee the integrity of either flake, we all agreed to weight the anchor as gently as possible while rappelling down the off-vertical runnel below. Our second anchor was the best, two solid wires in trustworthy black rock. Our last was the worst, a science project of far spaced pitons and tiny wires in ice glued choss. The fact we did not use any of the previously established anchors, and only saw two, is testament to the insidious terrain trap which is the Otterbody. Dozens of anchors have been placed on this route over the years, yet few remain. And of those remaining, all but one had a piece of previously fixed gear dangling loose. On the Otterbody, the Grand Teton reminds any and all jaded ski mountaineers of one thing: control is an illusion.

From our first turns on the East Face to pulling ropes on Tepee Glacier, three and a half hours elapsed. Fortunately, our conditions, timing, and weather forecast were perfect. Could we have gone faster? Certainly. However, maintaining a casual pace, keeping eyesight on each other, and documenting the adventure while savoring every turn, increased the value of this sacred ski mountaineering descent. I’ve heard many horror stories of chaotic Otterbody descents amidst warming conditions. Down-climbing bulletproof snow and dodging overhead artillery fire almost seems standard. One particularly unnerving tale, briefly aforementioned, told of a team using a single piton anchor to save time in the face of rapid warming. Another told of as many as six rappels. A third told of using slotted skis to belay a down-climb to reach fixed anchors guarded by ice. None of these scenarios happened to us. We kept skis on for the entirety of the route, had ample time to build sturdy anchors, and enjoyed every turn along the way. I even called my girlfriend from the Otterbody itself, while waiting for Hayden and Julian to finish rappelling and coiling ropes. As a budding ski mountaineer, she enjoyed being part of the adventure, and I enjoyed bringing her along.

When I reflect on our Otterbody experience, I couldn’t be more satisfied. For the past ten years of skiing in Grand Teton National Park, I’ve wondered how it would feel to make ski turns on the East Face of the Grand Teton. Having now made those turns, I can tell you: it’s wild. Furthermore, I couldn’t be more proud of Hayden and Julian. The bonds forged between partners on technical ski mountaineering descents of Otterbody magnitude are uniquely strong. I look forward to more adventures with these two in the years to come.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Range Meal Bars, The High Route, Black Diamond Equipment and Barrels & Bins Natural Market.

subscribe for new article updates – no junk ever

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.

Hello! Wow. Wh

LikeLike

Thank you 🙏

LikeLike

Incredible. One of your best trip reports thus far.

LikeLike

Thank you Eva!

LikeLike