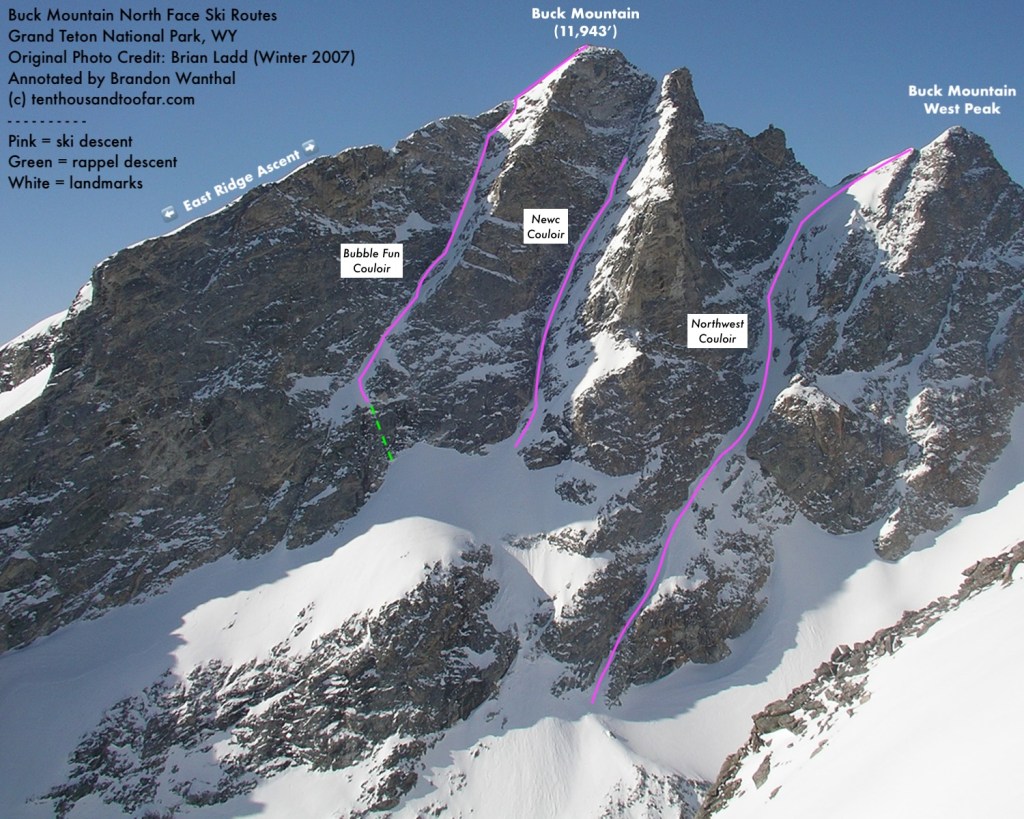

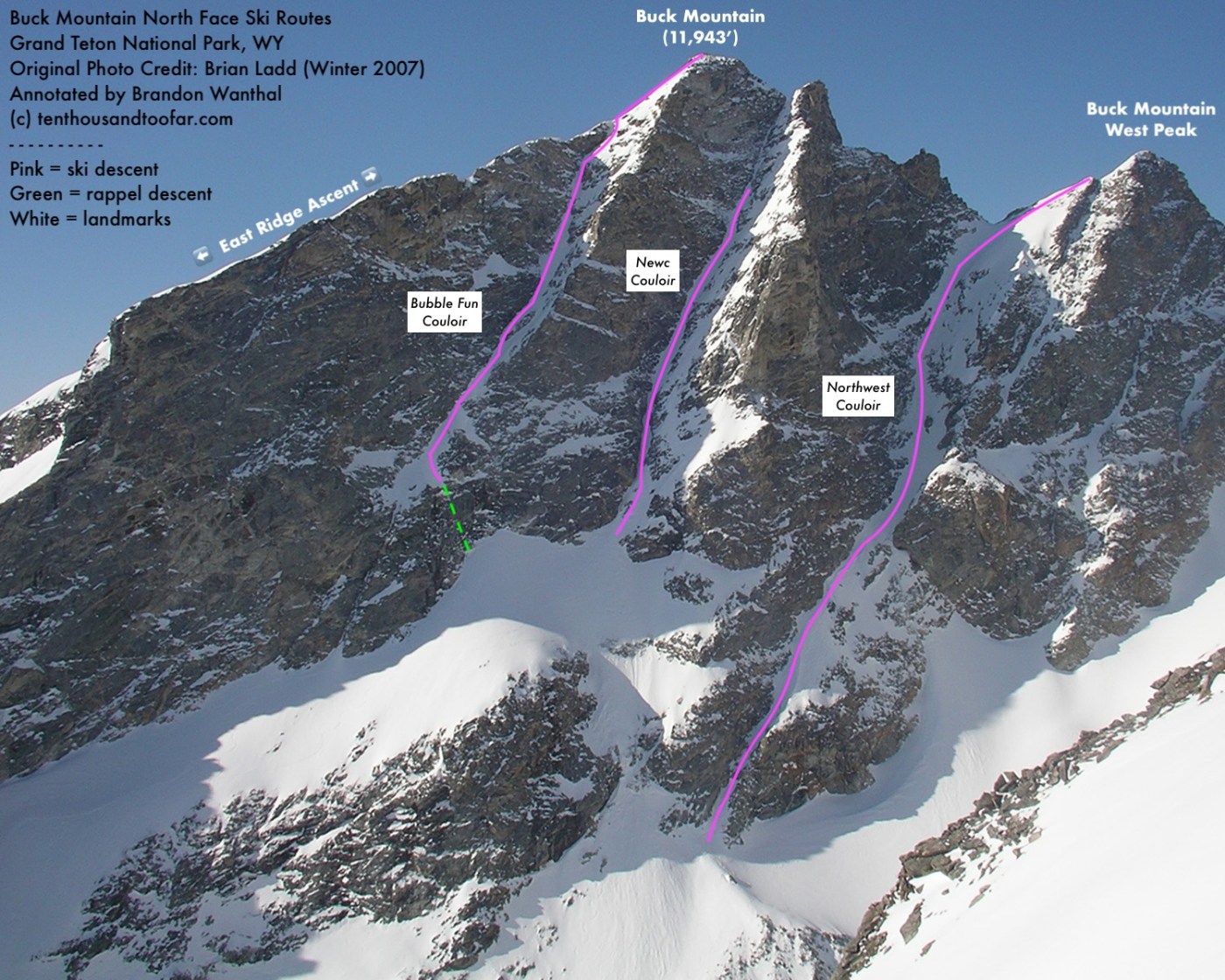

On May 20th, 2024, I made the third descent of the “Buck Triple”, linking the Bubble Fun, Newc and Northwest Couloirs for a near 8,000 foot day of tremendous steep skiing on the north face of Buck Mountain. From what I can gather this is the first time the Buck Triple has been completed solo, and the third descent in total.

Skiing the Bubble Fun Couloir with Hayden Evans earlier this winter was a benchmark achievement in my personal ski mountaineering journey. I was no stranger to complex and consequential terrain, but this thing was steep… really really steep. Hayden and I scored excellent conditions, enjoying supportable powder through the 60 degree crux to the bitter precipice of a sweeping 200 foot terminal cliff. This was Teton ski mountaineering in the truest iteration – at least in my mind. Ever since March 25th I’ve stared longingly at the other two commanding couloirs on the north face of Buck Mountain, neither of which I’d yet to ski, fantasizing about linking all three together in a single tour. While the Newc and Northwest certainly deserve their salt, and the Newc may even hold a steeper average slope angle than its easterly neighbor, the Bubble Fun was my mental gatekeeper to this epic project, and now that gate was kicked ajar. The “Buck Triple” was first completed by a three man team of highly reputed local mountain guides in 2020, and saw a second repeat by another duo of mountain guides earlier this year. For a north face which has been called “one of the most compelling visions in the Northern Rockies”, located within a few hour’s walk of a National Park trailhead, visible from the road and gawked at by thousands of backcountry skiers every season, the lack of traffic in all three lines, and exponentially less descents of the Triple, can only mean one thing – not only are each of these lines the real deal in their own, but skiing all three in a day’s work just isn’t something that bubbles to the forefront of many minds.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

I used “fantasizing” in the above paragraph literally. Dozens of mornings were delayed by daydreams dissecting the minutia of the Buck Triple – how I would transition between each line, the bare minimum gear needed and the optimal weather for a full day spent beneath such a foreboding north face. I imagined a partner descent as well as the feeling of skiing into the Bubble Fun solo, two 60 meter ropes in tow, casting down the hanging abyss that once characterized the limit of my ski mountaineering ambitions. I packed my bag and practiced faux jump turns in my living room – how did the swing weight feel? I even bought a new pair of skis inspired by my lack of confidence in the Bubble Fun crux, as my 185 centimeter, 101 millimeter waisted and relatively stiff sticks induced claustrophobia for the very first time in five years of chasing couloirs. As other springtime missions took precedence and the snowpack gradually dwindled I all but shelved this dream for another season, but then the Tetons caught yet another resurgence of winter. Alpine lows plummeted into the teens and winds accelerated. In an eerily similar style to Hayden and I’s March descent I recognized cold temps and cloud cover as my ally for keeping the chossy north face of Buck Mountain, and the exposed solar slopes overhanging the Bubble Fun and Newc Couloirs, glued together. A last ditch shout for a partner echoed silence. I was on my own.

The van registered 26 degrees in the summer Death Canyon lot, and with an alpine forecast for intermittent cloud cover and overnight lows around 22 degrees I took full advantage of a casual start. I rose at 3:45AM and savored a scenic dawn-lit commute over Teton Pass and along the winding Moose-Wilson Road while getting jazzed on a Colin Haley interview about his cutting edge winter free-solo of the Supercanneleta Route on Patagonia’s Fitz Roy. Listening to podcasts from the great soloists of our generation, whether it be rock climbers, alpinists or occasionally ski mountaineers, the morning before my own intense solo experience has become somewhat of a ritual. Before attempting the second descent of the North Face of Mount Wister it was the warming positivity of Peter Croft that accompanied me to the lot. Other classic figures such as Alex Honnold, Brad Gobright, Jim Reynolds, Will Stanhope and John Long frequent my stereo on these mornings. I never needed a headlamp as I hiked the summer Buck Mountain trail in ski boots past the Albright meadows and into Stuart Draw, finding a continuous snow-line remarkably early around 8,000 feet. I pounded past the venerable Peaches buttress and through the steep headwalls of Stuart, up the always remarkably exposed and beautiful East Ridge of Buck Mountain to the familiar 11,943 foot summit at a few minutes under the four hour mark – gravity had a lesser effect today. The sun sifted through intermittent clouds alongside a back-current of gentle wind, providing ample lighting for proper depth perception but minimal snow surface softening, perfect for an expedient climb and safe north facing descent. I clicked into my skis on the summit before 10:00AM.

Having thrown snowballs into what appeared to be an unforgivingly firm Bubble Fun from the East Ridge during my ascent I was leery of conditions, but decided to proceed with full intentions on reascending as soon as matters turned unruly. I skied a few pleasant turns of baby corn on the upper East Face before delving north into the Bubble, where I was met with firm but edge-able conditions that beckoned “one turn at a time” skiing. A short traverse leads from the entry snowfield into the tight, steep and unforgiving main couloir, where conditions gradually softened to dust on soft crust. Turns in this section were tactical and intentionally placed, separated by as much side-slipping as needed – I believe I made six turns in the 100 feet before the crux. The slope angle holds strong in the mid to upper 50 degree range here with an average couloir width constricting towards ten feet, meaning new snow is almost consistently getting sloughed downhill creating a slight tube-like runnel waiting to grab the tips of a sloppy turn. The crux is met about 150 feet into the couloir, a choke with an often exposed rock slab where Zahan Billmoria measured a slope angle of 60 degrees on a partial ski descent with the late Steve Romeo, and the couloir width pinches down to barely ski width. On my first descent I down-climbed a few body lengths in this section, but armed with shorter and more flexible planks I was able to negotiate this sector, including a protruding granite fin that required “dry skiing” antics, with skis on. Through this whole process I rationalized continuance because the crust remained edge-able and the surface snow gradually deepened, and my persistence was rewarded below the crux with 6-8 inches of supportable May powder that allowed me to release tension and enjoy exactly what I came here to do – link some well placed ski turns in an amazing location. 300 feet of perfect steep skiing led to the exposed exit ramp where I was ambushed by barely edge-able glaze above the iconic sweeping 200 foot terminal cliff. I considered bailing, but also knew the anchor was all but a 200-ish foot horizontal traverse away, and with a reduced slope angle and East Coast upbringing I felt comfortable relying on my edges, whippet in hand, to carefully scratch over to the anchor. I managed two turns in slough pockets through this traverse, mainly to relieve muscle tension in my uphill leg, and opted for a different anchor 60 feet above the one Hayden I used at the very edge. Since my minor fall in Wister’s Northwest Couloir I’ve made a conscious effort to chose security over style, and with splotches of blue ice exposed nearing the toe of a surely fatal fall the decision to bust out the cord early was easy. One short single rope rappel and one full 60 meter double-rope rappel landed me at the apron of the couloir for my second time. Despite variable conditions, I was totally stoked.

The exits to the Bubble Fun and Newc are all of a few hundred feet apart, making for a painless transition. I stashed as much gear as possible at the base of the couloir, tightened up my crampons and got straight to climbing. The Newc is the most channelled of the three, with substantial overhead hazard from a northeasterly wall, so I was excited to forge up with little pause while thick cloud cover kept the mountain intact. I was dismayed to find a gruesome display of exposed 50 degree rock, neve, debris and splotches of alpine ice in the very narrow lower couloir that made for compelling climbing, but obviously unattractive if not entirely impossible skiing. I once again pondered bailing before resolving to continue with the Bubble Fun mantra – I could always retreat, maybe it will get better? The inhospitable icy mess gave way to a stout breakable crust, which magically dissolved into the same boot deep chalky powder of the Bubble Fun’s torso, all within 100 feet. I still had some 700 feet of brilliant skiing above me, of probably the most sustained steepness I’d ever skied, and immediately was reassured the ensuing turns were well worth any smidge of down-climbing below. The pot of gold was here.

I reached the upper snow-line in the Newc at 12:10PM, about 180 feet from the geological apex of the couloir. Minuscule snow pockets amidst an overwhelming amount of exposed granite characterized the remainder of the couloir that was certainly unskiable today, but offered just enough white to ponder how high the Newc has been skied on the biggest of years. Has it ever been skied from the top? I doubt it, but never say never. The skiing was nothing short of phenomenal and SUSTAINED 55-60 degree hop turns for it’s ENTIRETY, in a couloir that dog-legs and pinches off at the bottom such that views of the exit are impossible! The exposure and deadly consequences of a fall are omnipresent with every flick of the hips, but after a half dozen tentative “hand-check turns” to catch my rhythm I broke into a steep skiing flow like I’ve never accessed before, weaving continual flowing turns to the pure sounds of Dorrigo by George Jackson and The Jaybird by Andrew Marlin. Skiing with music is a rare treat, reserved only for when I’m solo and have the utmost faith in conditions. Today the fiddle and mandolin tunes rang extra sweet. 800 feet below I hit the icy pinch where I assumed I’d have to down-climb, yet found just enough purchase for mindful side-slipping passage, whippet at the ready. I regained my stash and set intentions towards towards the final piece of the puzzle, the Northwest Couloir.

A quarter mile wide cliff underpins the Newc and Bubble Fun Couloirs, with an always all-snow exit east of the Bubble Fun and a conditions dependent exit direct fall-line beneath the Newc. With the Newc and Northwest separated by a piddly 200 linear feet, it’s exponentially more efficient to descend directly down from the Newc, however, after years of scouting this face I knew surprise cliffs and water ice often defy logic and obscure a clean ski line. Without recent beta I took the guaranteed route, skiing a roundabout half mile in a large semi-circle around the cliff, losing 200 extra vertical feet in the process, to reach the base of the Northwest Couloir. As I skied beneath the direct exit I was happy to see my suspicions confirmed – two relevant ice flows barred clean passage. I once again stashed nearly all my gear, picked some fiddle music and began a final pilgrimage to the sky.

Though probably the least challenging in terms of technicality, the 1,300 foot Northwest Couloir, also known as the West Peak North Couloir, is the longest of the three couloirs and still offers a fair shake of pucker. The upper couloir has similarities to the Bubble Fun, 700 feet of steeps underpinned by a sweeping 200 foot cliff matrix that requires a long rightward ski traverse with dire consequence to evade, yet unlike the Bubble a rope-less exit can be made via a sinewy 400 foot exit couloir. It’s a unique and totally rad line unlike any I’ve seen in the Teton Range. By 2:00PM I was standing at the top bathing in mythical views of Buck’s west ridge and the surrounding valleys amidst intensifying winds that signaled closing of another fruitful high pressure window. The skiing was on par with, if not better than, the Newc, and with a slightly diminished slope angle between 45-50 degrees I was able to really open up and ski aggressively. Nearing the cliff the snow became steeper and predictably less predictable, so I adjusted my pace to ninja turns, dancing down narrow grooves of wind plastered powder bisected by icy breakable crust, all while shimmering flurries of sun-illuminated May snow broke from the sky like confetti. The rightward exit traverse was “whippet-at-the-ready” business, but the exit couloir, where I once again thought I might have to down climb, skied something like baby corn after catching a few flits of intense afternoon sun. I let out a deep primal yell as I linked pleasant icy turns back to my cache. The Triple had finally fallen, a dream had been realized, and I was a bit more emotional than I’d like to admit.

Pleasant icy headwalls led to sticky corn led to log hopping… and swamp wallowing… and dodgy creek crossing… yep, I skied too low in Avalanche Canyon. My patience ran dry as I spent nearly and hour schwacking my way through muddy bogs better suited to alligators. I cranked the final three trail miles past dozens of tourists in my ski boots, which drew plenty of questions. The neuroma from thousands of hours of cramming my swollen toes into ski boots flared with tenacity. Thankfully, the two part hitchhike back to my automobile went smoothly. Ski mountaineering in late May is a different beast entirely, yet today the self prescribed torture registered closer to levity, lightened by one of the most magical days of my 29 years on this planet. In the following paragraph I’ll close with a brief story from my first attempt to ski Buck Mountain eight years ago.

A Short Reminiscence

In 2016 I went for my first ski tour in Grand Teton National Park. I rocked up solo with oversized park skier attire and four buckle Full Tilt resort boots – no walk mode. My touring setup was a pair of Marker Baron frame bindings nearly center mounted on a 128 waisted full-rocker Eric Pollard pro model powder ski (if you don’t speak skier lingo this translates loosely to ridiculously heavy and poorly matched gear for the objective, like trying to ride a 100 mile mountain bike race on a single speed town bike). My valiant goal was to ski the East Face of Buck Mountain, yet I wouldn’t even crack 10,000 feet. From the Bradley-Taggart Lot the naive eye can see the summit pyramid of Buck as an extension of 25 Short and Peak 10,696, an entirely different massif to the northeast separated by a considerable col. I had no ice axe, crampons, maps or beta – I was going to tackle the beast with crude line-of-sight tactics. Somewhere on the northeast ridge of 25 Short I lost my bearings and got suckered onto the steep north face where I encountered difficult climbing conditions. By the time I neared the summit of 25 Short, a blasphemous number of hours later, the sun had cooked the snow to potatoes and fortunately I had the sense to retreat. The next thing I remember I was sitting on the hood of my car dejected, demoralized and dumbfounded that Buck was so much further away than it appeared, likely sucking down a cigarette of defeat. Then Scott Palmer, a fellow co-worker at Grand Targhee, came skipping past my car with a shiny rope draped over his pack. I asked him what he skied. “The Grand” he replied relatively casually, “and you?” “I turned around somewhere along the ridge to Buck” I said, still unaware I had spent an entire day clawing up an entirely separate mountain, and slightly embarrassed given the impressive stature of the Grand Teton towering 7000 feet above my perch. At that point I didn’t even know the Grand Teton could be skied. Fast forward eight years and thousands of ski tours to May 20th, 2024 – things have changed – and maybe therein lies the greatest takeaway from this day: hard work, perseverance and passion pays off.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Barrels & Bins Natural Market in Driggs Idaho, Range Meal Bars from Bozeman Montana and Black Diamond Equipment

enter your email to subscribe to new article updates

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.

Leave a comment