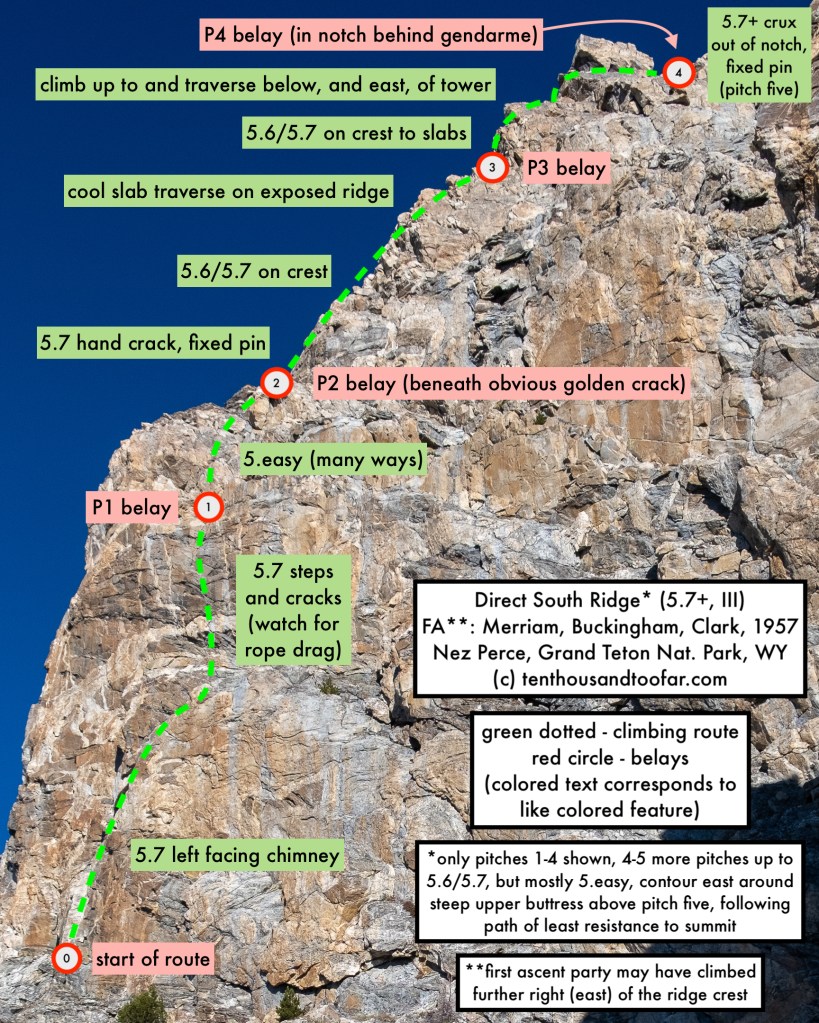

On Wednesday March 20th, Hayden Evans and I climbed the Direct South Ridge (5.7+, III) on 11,901 foot Nez Perce, and made a powdery ski descent of the North “Spooky” Face into the East Hourglass Couloir and Garnet Canyon, one day removed from a “calendar winter” ascent.

After my first ski-alpinism linkup of Irene’s Arete (5.8, III) and the Spoon Couloir on Disappointment Peak three days earlier with Chase Krumholz, I was left drunk on climb-to-ski fever. And to be quite frank, our Irene’s adventure just went too smoothly. In the two work days proceeding that all-time outing, I was left fantasizing about how to up the ante – a longer rock climb to a higher summit, and a more demanding ski descent. I didn’t necessarily want to increase the difficulty of the rock climbing, just the magnitude of the entire day. The Grand Teton would have been the obvious choice, but I found my attention drifting to one of my long desired remaining Teton ski descents – the Spooky Face on Nez Perce. “The Spooky” is a mythical descent with a regal presence, visible from just about anywhere north of Burnt Wagon Gulch. A careful look reveals a clear ghoulish face, with exposed cliffs forming the eyes, nose and mouth. It’s difficult to measure slope angles of these ephemeral lines on the internet, but a reasonable Caltopo estimate offers sustained gradients of 50-55 degrees on a 900 foot hanging snowfield – the stuff ski mountaineers with an affinity for high consequence jump turns dream about. Conveniently, an 1,100 foot, grade III, 5.7+ rock route adorns the peak’s sunny side – the Direct South Ridge, which I climbed in the summer of 2023 with Bobbi Clemmer. Hayden Evans cosigned my idea with little resistance, and together we set off from the Bradley-Taggart lot by headlamp around 6:00AM.

Edit: It’s worth noting that the standard winter route to the summit of Nez Perce is on the northwest aspect, not the Direct South Ridge.

Approaching the Direct South Ridge is arduous by summer, but thankfully slightly less so in winter. The climb is located one ridge west of the prominent southeast ridge rising from the saddle separating Nez Perce and Shadow Peak. We began the day by climbing to the skier summit of Shadow, traversing southwest and dropping into the basin underpinning the Sliver Couloir via a short north facing ski shot. We flipped back into climb mode and booted to the obvious col south of Nez Perce’s east face. From here the Direct South Ridge is visible, and a short traverse across the lip of a wind scoured couloir brought us to the toe of steep slabs defending a golden buttress overhead. In summer these slabs are an easy scramble to the rope-up-point a hundred or so feet above, but we found them quite wet and decided to bust out the cord early.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

Since I had climbed the route in summer, and Hayden had not, I led the first two pitches to establish us on the ridge. A short pitch of snowy vegetated slabs and tree yanking led to the proper first pitch, a left facing blocky chimney with a sparsely protected entry slab. This pitch dropped remarkably easy and boosted our confidence for the daunting wall overhead. Hayden led pitch three, beginning with a few steppy 5.7 dihedrals oozing fresh meltwater that quickly devolved into scrambling terrain, a full 50 meters to a nice belay beneath an attractive headwall of vertical cracks on the crest. Pitch four was and always will be the gem of this route, a standout 50 meter pitch of remarkable exposed crest climbing reminiscent of Irene’s Arete, beginning with a beautiful yet far too short 5.7 hand crack. By now spirits were soaring, and I greatly enjoyed running the rope far between protection points, finding a flow of notable proportion. The pictures from this pitch are some of the most photogenic you’ll find in the Tetons.

Two more pitches on the direct crest, including one particularly difficult, gently bulging, 30 foot crack on pitch six, took us to the snow-line where progress grinded to an immediate halt. I tried to find a dry way around the snowy ledges to no avail, and facing no other option we switched back into winter mode. A long simul-climbing pitch of snow and juggy mixed climbing in ski boots and crampons ended at a final imposing headwall impeding progress to easier soloing terrain above. I was cursing myself for not having steel toed crampons as I pushed the limits of my Petzl Leopards far beyond their intended purpose. The terrain would have been trivial in rock shoes and summer conditions, a handrail traverse to a small roof pull, and subsequent friction slab – maybe 5.6 – but much of the rock was glazed in verglas and my dull aluminum crampons struggled to find purchase on the knobby, elusive edges. Augmenting the problem was a severe disparity in protection – the whole fiasco felt pretty serious, complemented by a marginal belay of a tipped out #4 Metolius Cam and a medium stopper wedged between crystals in a thin seam on the only available rock island. Hayden did an excellent job resisting a serious swinger that could’ve threatened our belay, despite his non-existent mixed climbing experience.

After our two belayed winter pitches we packed the rope and began cutting a heartbreaking trench through unconsolidated sugar snow to the summit, tackling a handful of rock bands along the way. Wallowing in thigh deep snow, and occasionally punching to belly button, was the lowlight of our day. Dangerous you may ask? Well, maybe if we plunged into a slot between two talus blocks, but the snow lacked a cohesion or density indicative of wet slab or glide avalanches. A dumb luck concoction of daytime intermittent clouds and unforecasted moderate winds, combined with late afternoon recrystallization, preserved snow surfaces just enough to rationalize continuance. With fortitude we took turns blasting our way to the summit, veering for dry rock whenever possible. One particularly steep step offered a few gratifying pick sticks into a mushroom of rotten water ice while stemming between pleasantly spaced rock edges at 11,800 feet, suspended high above the material world below. We topped out at 5:00PM, about two hours from sunset. Our celebration was brief – it was time to ski.

Surprisingly enough, hearing the melodic click of my heel pins as I stepped into my skis was the finest dose of Xanax I’ve ever taken. After a full day of frenzied verticality, including ~6,000 feet of total climbing, six rock pitches, two mixed pitches and hours of winter mountain slogging, I was finally back in my element. The exposure of the slope hardly registered as I sunk into the rhythmic dance of steep jump turns. Despite the face getting skied three times in the week prior, we found ample fresh snow on the margins and near cliff edges. I believe this was the steepest and most exposed face Hayden had ever skied, and he handled the work with poise. The line appears more straightforward than it actually skis – a chutes and ladders style descent of discontinuous faces, couloirs, slots and traverses that terminate at the precipice of a 200+ foot cliff. The jump turns nearing the edge were some of the finest of my career, and we made a point to milk every last possible one. By the time we reached the anchor a steady plume of blinding spindrift was blasting up the East Hourglass Couloir as light faded drop by drop from this special Wednesday. We tossed ropes with little delay. Our time was now.

We had nobody to blame but ourselves when our ropes came up at least 60 feet short of terra firma. Dangling at the knots of our 50 meter lead line panning for cracks, I thought my weight saving nonchalance of disobeying the standard double 70 meter Spooky Face rope beta was about to earn us a one way ticket to headlamps. In a last ditch effort I pendulumed east and found an intermediate anchor in a steep ice gully just out of reach. The mountain gods had our backs today, as I was barely able to reach the anchor with the basket of my ski pole, draw it close enough to clip a runner from my belay loop to the master point, untie my stopper knots, gently rappel off the end of the rope and slide onto the anchor with minimal force. Hayden did the same, and since we had a 60 meter tagline we were able to retrieve our system easily. One more shorter rappel brought us to a wind chalked East Hourglass Couloir, a bonus 1500-ish feet of soft jump turns into the safe, familiar, icy annals of Garnet Canyon. We skied truly bulletproof glaze to the lake and reached the car at 8:00PM, 14 hours after departure, smiles brighter than the most golden of granite we touched all day.

Reflection & Rack/Gear

Surely in the future this quirky activity will meet its match, yet once again our day flowed so well it almost seems like a rock and ski marriage was destiny. We kept a fast pace on the rock, climbing the first six pitches in about three hours and change. The true time handicap came at the hands of snow wallowing and icy slabs – ironically, the standard ascent faire associated with higher end ski mountaineering. We believe this is the first time the Direct South Ridge (5.7, III) and Spooky Face have been combined. My only hope is this article inspires many more. This adventure joins the growing list of “best day ever’s” from March 2024, and hopefully serves as a spring board for even more vertical weirdness.

For technical gear we carried Metolius Ultralight Cams from #3 to #7 (fingers to two inches), a trim selection of nuts, six alpine draws, one 120cm Dyneema sling and one 240cm Dyneema sling for anchors, a 50M triple rated 8.7mm lead rope, a 60M 5mm tagline, aluminum crampons, ski-mo harnesses and one lightweight axe each. We traveled light and committed in terms of layers and provisions. Kuddos to Hayden for dragging 4FRNT skis, four buckle boots and Marker Kingpins to the summit, but I went much lighter with Scarpa F1 LT’s, Icelantic Natural 101 skis and light Dynafit tech bindings. The only things I would change is bringing an extra pair of gloves (I only brought one pair, and my hands got quite wet during all the snow climbing), and swapping our ropes to allow for at least a 60 meter rappel. I guess steel toe hybrid crampons could have been nice too.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Barrels & Bins Natural Market in Driggs Idaho, Range Meal Bars from Bozeman Montana and Black Diamond Equipment.

subscribe to support the flow, and for new article updates

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.

Leave a comment