The Snake is a challenging four pitch outing in the deep caverns of Cascade Canyon, defended by a 6.5 mile trail approach that deters most parties for the length of the route. That said, it’s a logical and attractive line on mostly sound rock, with two pitches of difficult 5.10 climbing.

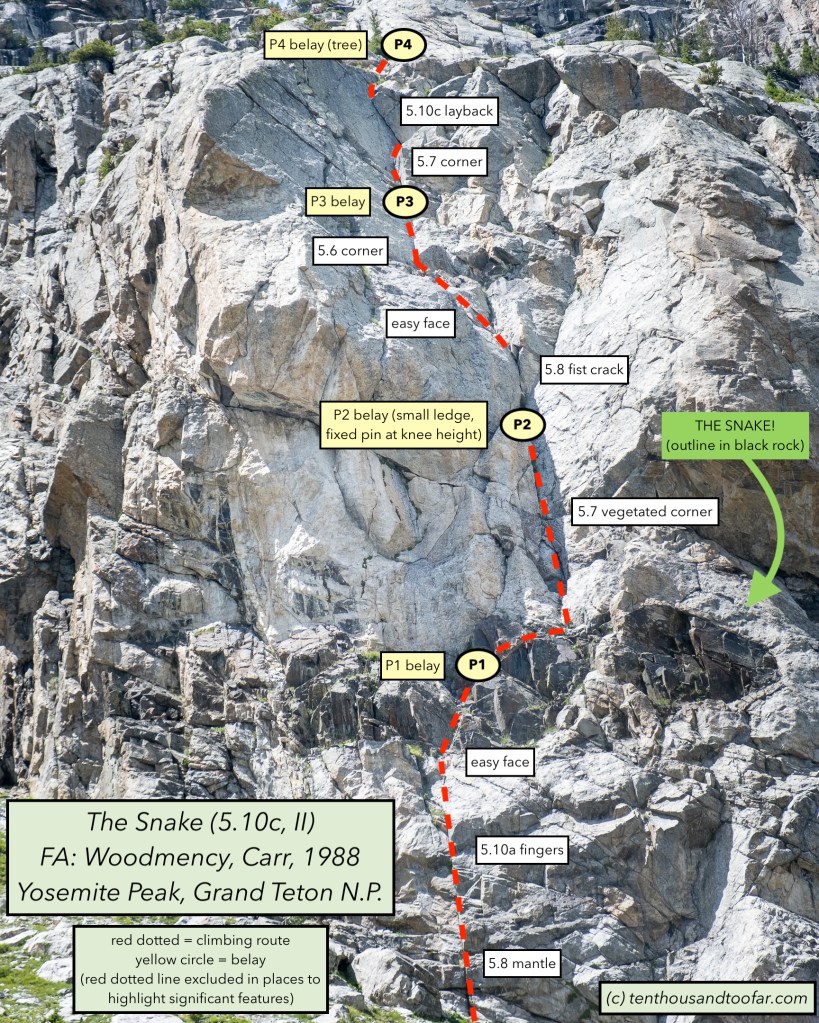

Established by Jim Woodmency and John Carr in 1988, the Snake is a difficult outing that packs a punch for 520 vertical feet. The route has a good variety of climbing styles – a spicy mantle right off the ground, 5.10- finger crack, 5.8 fist crack and a bold 5.10 layback finish, with ample 5.7 chugging between. Named after a large black-rock snake imprinted at the base of the climb, visible from the Grand Teton let alone the approach trail, The Snake also brings mysticism. While ~6.5 trail miles from String Lake (or five-ish from Jenny Lake boat dock) may be a deterrent for just four pitches, only a generous 10 minutes of off-trail scrambling is required, keeping the approach shorter than most climbs of closer linear proximity. Jed Porter was my partner for this outing, an off-duty tenured Exum Mountain Guide, and with some ten-fold less years rock experience my aim was simply to keep up. Ironically, The Snake would also be the most grade-difficult alpine climb of my life.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

We caught the second boat from Jenny Lake and enjoyed a morning cruise to the west boat dock and mouth of Cascade Canyon. This was my first time on the iconic Jenny Lake boat – what wonderful scenery, and the Thursday air was crisp as could be. We made expedient time up Cascade and into the South Fork, locating the base of the climb quite easily by climbing to the second significant switchback and spotting the dead evident snake in shattered black rock. Sometimes the “things” people see in rock formations are a stretch, but this time a snake’s head and neck were clearly outlined – black against white – with a large pale rock as the eye. We briefly scouted descent options, stashed gear and scrambled to the base with a mix of Mountain Project and Ortenburger-Jackson (OJ) beta.

The most difficult pitches were first and last, with filler climbing on pitches two and three. Nervous to lead old-school 5.10- straight off the deck I passed the first lead to Jed, resigning myself to the crux 5.10 layback pitch above – at least I would be warmed up. Jed began with a smooth lead over a tricky mantle (5.8) and through a left-facing finger crack dihedral (5.10-) with sustained technical stemming and some long reaches to good locks. This pitch was ultimately more manageable than expected for the grade and date of first ascent, a trend that would continue for the rest of the climb. From a belay in the shattered black-rock body of the snake, I traversed hard right for the second lead, eventually gaining an obvious 5.7 dihedral which I followed for about 100 feet to a small belay stance with a fixed pin at knee height. Though vegetated, pitch two offered some great opposing movement for the shoulders, on sound rock with occasionally sparse but adequate protection. In a blink we were halfway up the wall.

Jed swung for pitch three, which ascends an obvious textured and bulging wide crack some 20 feet above the belay. I found this crack surprisingly difficult, which oscillated from thin fists to cupped hands with a few small face holds. Above, wandering slab climbing gently left to a clean 5.7 corner capped another memorable pitch. The final lead was the crux, which began up more gentle terrain overshadowed by an intimidating left leaning layback crack above. A comfy no-hands rest before the action provided the perfect setting to plot my demise. For those who know me, laybacking, and powerful climbing in general, is not my forte – and 5.10c, the ultimate grade we gave this pitch, would be my hardest ever traditional lead.

My first attempt was overly cautious. I was scared, fired in a cam as soon as the climbing became 5.10 and took a seat. I was a little embarrassed, but also unwilling to risk a ledge fall 400 feet off the ground and hours into the backcountry. From here I projected the crack, eventually connecting a sequence of tenuous laybacking up slick speckled rock, through the ultimate crux and into a good resting stance. I let out a holler, arranged some solid gear and fired overconfidently into the final tricky bit, a steep roof mantle that marks the end of the 5.10 climbing, popping a foot and floating into clean air – caught by a lovely #0.75 cam. I hung my head only long enough for Jed to generously suggest I lower back to the belay and give it a second burn. On my subsequent push I committed to climbing with conviction, and fired the pitch with only two pieces of pre-placed gear, minimal resting and a head full of steam. We topped out in the early afternoon beneath crystal clear skies, with views of the impressive northwest Enclosure, Grand Teton and Middle Teton ice routes overseeing every bite of my sandwich.

To descend we followed faint whiffs of climbers past through easy fifth-class terrain, beginning above and climber’s right of the final belay tree and traversing up and gently left along the path of least resistance to the broad sloping bench just south of the climb. Though the OJ guide mentioned something about a descent gully, the two gullies south of The Snake seemed overly loose and unlikely. Instead we descended the broad bench generally southeast until a logical descent could be made through gentle forested terrain back to our gear cache just off the S. Fork Cascade Canyon summer trail. All in all this climb passed in somewhat of a blur – maybe that’s just what happens when you climb with a professional mountain guide of 20+ years experience. Jed just always seemed three steps ahead, with perfectly managed belay stations, quick changeovers and the agility of a mountain goat in kitty litter fourth class terrain. Furthermore, his willingness to let me project, untie and pink-point a pitch he could’ve easily on-sighted is a testimony of character. Freeing the hardest crack of my life, deep in the Teton backcountry with such a humble new partner sealed the stamp on a day to remember, let alone four great pitches of memorable alpine granite.

Route Summary, Rack & Thoughts

We clocked about eight hours dock to dock, projecting, lunch breaks and water stops included. The OJ guide suggests Grade III, but Grade II seems more than appropriate. Given the ambiguous original grade of “5.10”, we felt the crux pitch was modern 5.10c. The pitch lengths provided in the OJ topo seemed spot on, and if anything the grading felt slightly soft. Our consensus grade opinions are reflected in my annotated topo. We climbed on a 50M rope and brought a double rack of cams to three inches, with one #4 BD Camalot per guidebook suggestion. If I were to repeat this route I would drop the at least the #4 (never placed it), and maybe the second set of finger cams. There is some loose rock on the first two pitches, but generally the rock quality is high and the belay stations sheltered. We called The Snake a “second tier Cascade classic” – a slightly unfavorable hike/climb ratio, and not quite Guide’s Wall cleanliness, but definitely a scenic, sustained and challenging outing in a unique nook of Grand Teton National Park that deserves more pairs of rock shoes. Bonus points for clean falls on the crux pitch and epic views of the intimidating west faces of the core range.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Barrels & Bins Natural Market in Driggs Idaho, Range Meal Bars from Bozeman Montana and Black Diamond Equipment. Give these guys some business – who doesn’t need great skis, gear and wholesome food?

If you would like to support Ten Thousand Too Far, consider subscribing below and/or leaving a donation here. The hours spent writing these blogs is fueled solely and happily by passion, but if you use this site to plan or inspire your own epic adventure, consider kicking in. A couple bucks goes a long way in the cold world of adventure blogging. I also love to hear your thoughts, so don’t leave without dropping a comment! Thanks for the love.

Follow my photography at @brandon.wanthal.photography

enter your email to subscribe for new articles

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.