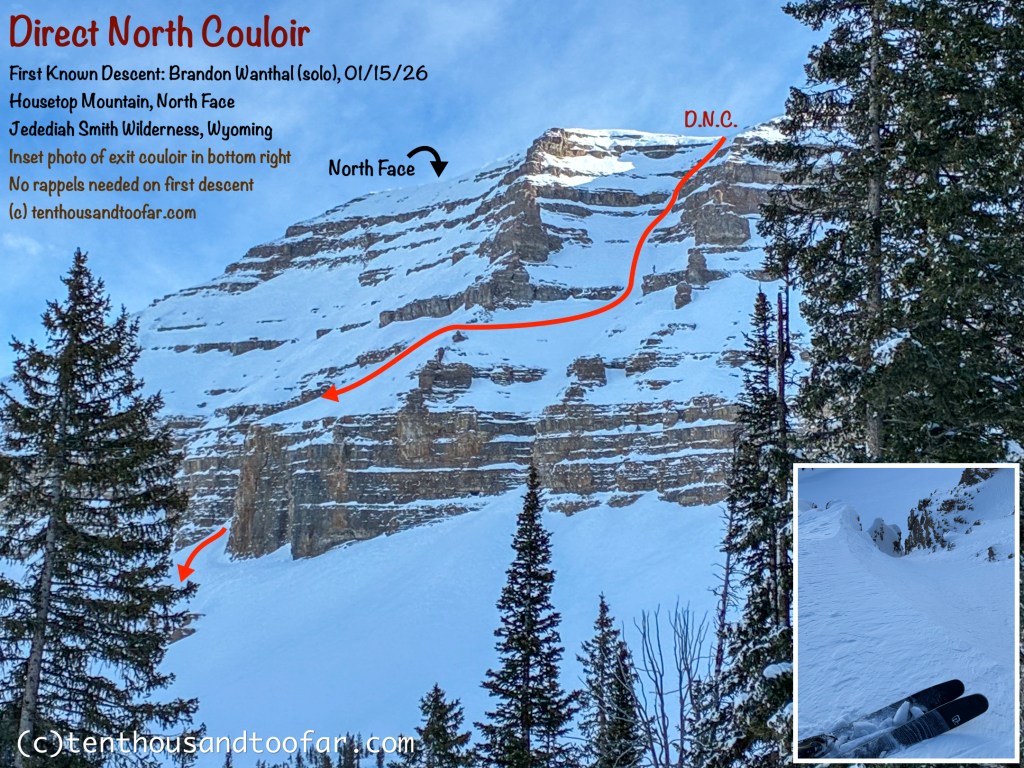

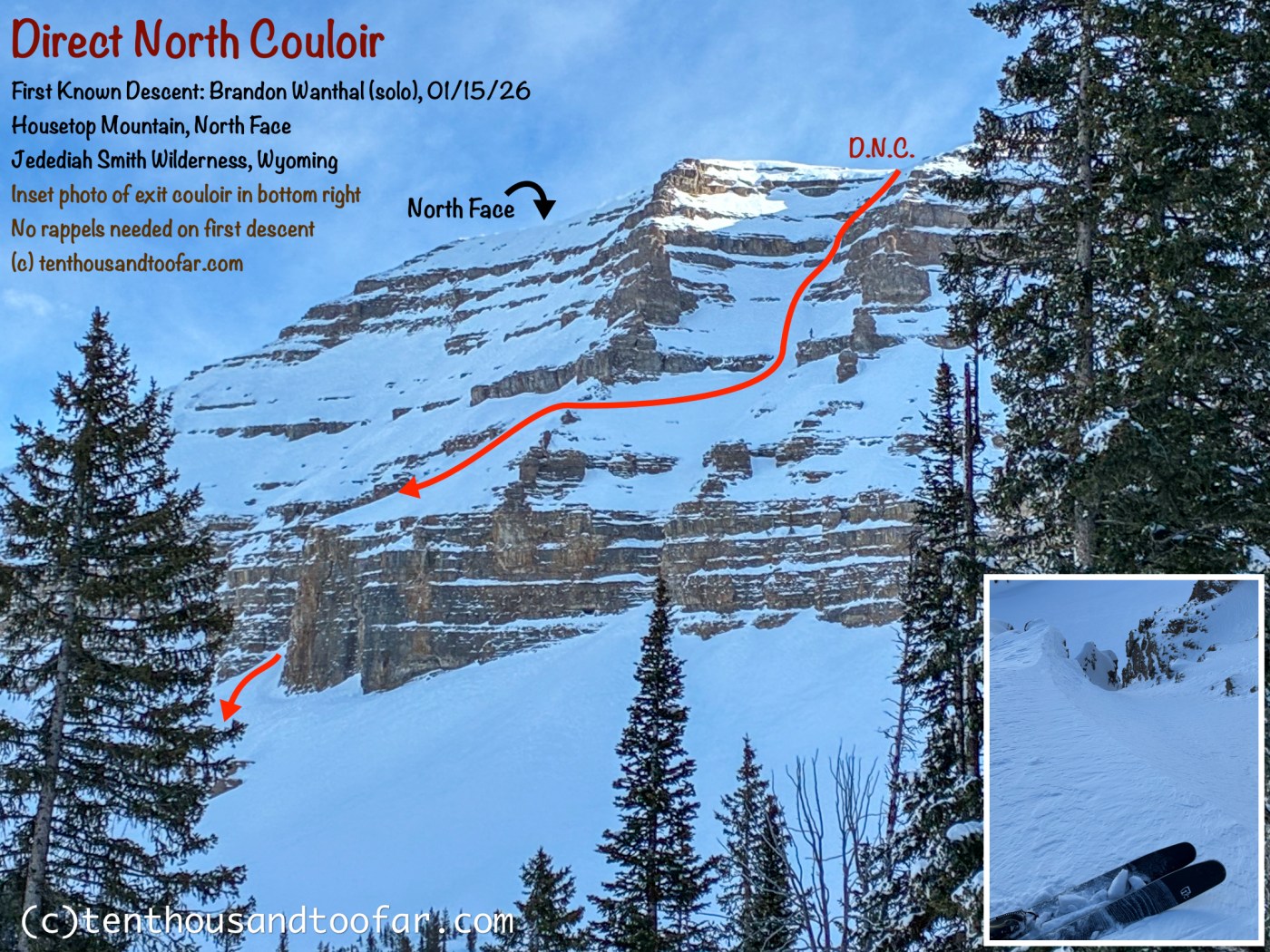

On January 15th, 2026, I skied a potential first descent on the North Face of Housetop Mountain, the most alluring and rarest skied north face in the west Tetons. It’s difficult to know exactly what has and hasn’t been skied on the heavily gate-kept west slope, but longtime area record keepers and ski mountaineers believe the line to be previously unskied.

The north face of Housetop Mountain is the steep skiing crown jewel of the west Tetons, an awe inspiring 900 foot face hanging above a half mile wide cliff with one single break, visible from the valley floor. Before I skied the Direct North Couloir, the only known route on the face was the “North Face”, an ephemeral quest beginning at the true summit, weaving through a maze of shorter horizontal breaks without exact definition. Unfortunately the North Face is rarely in condition and descents are spaced by many years, if not decades. The upper face is very steep and often windblown, thereby peppery, and capped with dramatic cornices. It often looks better from the valley than the summit. I attempted the route last April but bailed to the classic East Couloir due to poor coverage. On egress I spotted what would become the Direct North Couloir, beginning 600 feet down the west ridge. This was the only other ropeless passage onto the half mile wide north face. Conferring with elder statesman and record keepers of Teton ski mountaineering, it appears this striking line hadn’t been skied. The entry was steeper than the North Face, with pitches in the 55 degree range. West wind crossloading, a bony crux, large cornices, severe exposure to several terraced cliffs, and a long eastward traverse to the face’s sole exit couloir compounds intimidation. To make matters worse, a rope isn’t much help. Unlike the granitic peaks of Grand Teton National Park, Housetop’s north face is mountain limestone of the crumbliest variety. Anchoring opportunities in the fractured, blocky and down-sloping dolomite are fickle if existent at all. In classic west Teton fashion, what the Direct North Couloir lacks in vertical relief is compensated by complexity, intensity and adventure.

On January 15th, two days after doing the first descent of The Blue Line in Grand Teton National Park, I packed a slim rack of three pitons, six wires, and a 65 meter rope to the 10,540 foot summit of Housetop Mountain. I didn’t think I’d need the cord, but couldn’t be completely positive, as the exit couloir can’t be scouted from anywhere within a sane day’s walk. Despite a relatively pedestrian elevation, Housetop’s standard approach via the west ridge is long and barred by many pesky sub-summits. A vicious north wind and pessimistic reports from other area skiers had me doubting conditions for a line this consequential. My dream was settled high pressure powder like I had on The Blue Line. As I threw cornice chunks into the Direct North Couloir, which looked a wee bit thin anyways, I realized the work would be scratchy dust on crust. From the true summit I called my fiance to tell her I was bailing. “A younger Brandon would do it, but I just don’t know if I want to”, I said.

As I snacked for my third time on the impressive summit, my thoughts wandered back to the couloir. Perhaps it wasn’t as steep as it appeared? Maybe the snow would get better lower? The upper pitch looked outrageously steep for firm conditions, but I’ve also had several times where scary descents feel substantially cozier once clicked into skis. I slid back down the west ridge with an open mind, calibrating my steep jump turns on icy south facing wind drifts. A high right wall above the couloir allowed space for two tight turns before full commitment. If I didn’t like the surface I could easily traverse out. I made the turns and was surprised to feel my ski edges bite like crampons. Below the inch of windblasted dust was a sticky soft crust, like a resort groomer on a 32 degree morning. I got goosebumps, traversed out of the couloir, and shimmied into my harness for the main event.

As expected, gentle turns off the ridge quickly rolled into sustained 50 degree jumpers above wicked exposure. Quickly I encountered the crux, a craggy mess of sloping limestone with a tight bypass of fluted snow skier’s left. Reaching this hallway involved shuffling over streaks of blue water ice, and power sliding a 60+ degree wind drift. In mid-winter this crux could very well fill in for more fluid skiing, but this face is notorious for holding very little snow, so who knows. I began linking turns again twenty feet lower, where I enjoyed 500 feet of spectacular orange peel powder skiing beginning with steep jump turns and ending with linked high speed carves, some of the more spectacularly positioned skiing of my life. At the base of the face I sniffed out the long eastward traverse, a scenic 150 foot glide on gently sloped terrain towards the exit couloir. The worst part of this traverse was not the traverse itself, but rather, an unsettling feeling that the sinewy exit may not be filled in. A sharp dogleg barred scouting from above, but turn by careful turn a secret passageway revealed itself. Milky buffed powder ushered me to the canyon bottom.

When talking first descents in the Tetons, especially the heavily gate-kept and poorly documented west slope, it’s important to acknowledge historical gaps. While folks who have resided and skied in the west Tetons longer than I’ve been alive are confident the Direct North Couloir has never been descended, certain resolution is impossible. When reflecting on my experience, the distinction between a first, second or third descent is far less important than the empowering feeling of making ski turns on a mythical face I’ve envied since arriving in Teton Valley eleven years ago. The Direct North Couloir has utility both as it’s own descent, and as an alternative to skiers seeking the rare North Face.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Range Meal Bars, The High Route, Black Diamond Equipment and Barrels & Bins Natural Market.

subscribe for new article updates – no junk ever

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.

Leave a comment