On Saturday June 24th Bobbi Clemmer and I got benighted on a wild ascent of a wet Trinity Buttress (a.k.a. Symmetry Crag 4). Originally graded 5.9 by Yvon Chouinard and T.M. Herbert in 1970, the climb ascends two-thirds of the major rock buttress west of the popular Guide’s Wall with a few stellar, and a few not so stellar, pitches.

The south buttresses of Cascade Canyon host some seriously impressive rock formations, home to the ever popular Guide’s Wall and a fair number of semi-trafficked moderates. While still waiting for the true alpine to dry Bobbi and I planned to check out Vieux Guide, a four pitch alternative to Guide’s – a mellow day focused on improving alpine efficiency and enjoying some time in the early summer sun. Instead, after heavy rain and snowmelt left the crux pitch of Vieux visibly streaked with water, we pivoted and aimed for the lesser-known Trinity Buttress (a.k.a. Symmetry Crag 4). Trinity is located just west of Guide’s, and the crux pitch of the route we planned to try, “A Climb On Trinity Buttress”, seemed dry from the approach trail. We had actually attempted the route a week prior, bailing before pitch one for a multitude of factors, and were eager to give another whirl. The forecast was clear, the sun was shining and the line looked awfully proud.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

The route begins at the furthest west extremity of the buttress, in a clump of trees capping a grassy ramp barred by broken fourth class terrain. Much like our last attempt, these slabs were completely drenched and of the stiffer “fourth class” variety, so we pulled out the cord and belayed a brief pitch of wet choss before the real deal. Finding the route was easier than expected for an obscure non-classic. The 5.9 left-facing dihedral of pitch one can be spotted from the belay ledge, and a protrusion of low-angle rock steps provides the only viable passing of an otherwise overhanging cave. The pitch five 5.9 leaning dihedral is also easily identified from the approach. I tied in at 11:00AM and began leading up the bold and adventurous pitch one, which earns the 5.7R grade. Every other route in the Teton low-country begins with a runout slab, presumably the result of ancient glacial polish, and as time weans on I’ve begun to welcome the challenge as a warmup for both body and mind. 5.7 is an interesting grade for me, representing the grey zone between my soloing and definitive roped climbing thresholds. On this particular pitch I climbed about 80 feet of low angle bulging slabs with little more than a slung bush and a few shallow nut placements, wandering side to side whenever I saw a small slot for protection or the climbing felt too difficult, all while heading towards the obvious left facing corner that holds the “5.9 stem” crack from the original topo provided in the Ortenburger-Jackson (OJ) guidebook. Though appearing dry from below, the confines of the clean hand crack were very wet, providing both uninspiring jams and suspect cam placements. I fought tooth and nail to get up this one, stemming on interesting crystals and yarding on small crimps, for whenever I jammed or laybacked the crack I had to spend a few valuable seconds wiping my hands dry and re-chalking. The crux was towards the top, but luckily a few huge jugs appeared allowing a secure mantle into easier terrain and ultimately a small but cozy belay ledge with a healthy tree. I was amazed Bobbi managed to follow-free the beast, but reported a similar difficult fight, with just enough face holds to evade a wet demise.

Pitches two, three and four were all much in the same, rambling, vegetated and occasionally loose, all between 5.6 and fourth class. Pitch four was especially bizarre, a near 50M pitch that maybe gained all of 10-15M in elevation, traversing east across endless steep blocky terrain. As a budding adventure climber accustomed to more sanitized routes, Bobbi displayed excellent poise navigating the the loose and dirty terrain with swing fall potential, and by 4:00PM we were oriented beneath the crux pitch, ropes flaked and ready for action. We lost significant time to route finding.

Pitch five, the crux, almost makes this climb worth the lower, less-savory fare. The golden, right-facing, arcing, dihedral is striking, 40 some meters of consistent vertical or overhanging “5.9” jamming, laybacking and stemming with superb exposure. About halfway through the crack seizes to millimeters for a few body lengths, where the OJ topo indicates the use of RP’s and the corner gets particularly clean on dark reddish rock. This also happened to be the first place where face holds, not just cracks, were streaked with water. Staring down an un-jammable corner full of wet smears near my free-climbing limit, protected by a single offset aid nut not rated for lead falls, I eyed the one magically dry hold – a twelve inch wide, two pad deep edge at chest height. After eliminating every other option I resorted to the most desperate free-move of my life, lurching from a wet left foot jam into a right handed inverted palm press on the two-pad edge, levering my entire body weight onto my right wrist, upper trunk pressed against the steep slab and left foot flagged into the corner for balance. From this outrageous position I was able to place a tipped #1 cam in a shallow mossy pocket above the incipient seam at full wing-span extension, latch a small wet crimp and try to match my right foot to my right hand, but I just wasn’t flexible enough. In a final act of primal panic I smeared my knee into the edge, fired my right hand to a saving jug, matched my left knee to my right and eventually mantled onto the edge. I truly couldn’t believe I was still on the wall, let alone by two knees on a near vertical slab, but had little time to regain composure as the pitch only continued to intensify. I did some lead nut-tool gardening to reveal edges needed to pass an undercling crux, and even girth hitched my prusik cord through a stopper to protect a second, and final, difficult undercling when I ran out of slings. I built a hanging belay behind a cello-shaped flake under the mega roof and finally, after nearly an hour, called off-belay. I thought this pitch was relentless and well within the modern 5.10- grade, but it’s possible the wetness skewed my impression.

The sixth and final lead began with a harrowing protection-less traverse onto a broken slab climber’s right of the dihedral, avoiding the mega roof, and finished on a final runout slab that only got sportier with every move, eventually necessitating cautious mud climbing in a low angle and actively dripping chimney with marginal protection (5.7R). According to the topo I may have set our pitch five belay too high and should have escaped onto the slabs earlier, however, belaying in the middle of these slabs would leave the final pitch belayer quite exposed to lead rockfall from the finishing chimney above. There is also ample small talus and kitty litter on an unsupported slope above the climb. When I topped out I rained some clementine sized artillery down the slabs, and while Bobbi was belaying pitch five a natural granite grapefruit came off this slope and struck a tree just behind her. I moved several large blocks on the slope below the final belay and redirected the rope meticulously to guarantee it wouldn’t tension against any widowmakers. There seemed many different ways to finish the final pitch of Trinity Buttress, but none appeared any better than the original line, which I believe stayed climber’s left. General alpine saviness and stable weather, both on the day of and leading up to the climb, are useful to make this a “safe” outing. We topped out with parched throats and frayed minds at 8:00PM.

Sadly, the story doesn’t end here, but I will keep the descent brief. We made the naive mistake of leaving headlamps on the ground to cut weight, and as the sun began to fade over the north shoulder of Mount Owen we found the recommended descent (via fourth class ledges to the final Guide’s Wall rappel) a little too exposed and convoluted for Bobbi’s taste. We had also run out of food and water hours earlier. suppressing energy. We traversed 90% of the way to the gully separating Trinity from Guide’s and used phone flashlights to make four double rope rappels from trees down the east end of the buttress, complete with some down-climbing, to our packs stashed near the Guide’s Wall approach trail. Turns out it’s pretty time consuming to, pull, coil, flake and occasionally untangle double ropes in pitch black fifth-class terrain safely with a single phone light, let alone down-climb intermediate wet slabs and rig anchors. We reached the packs not long after midnight, but besides a bruised ego we had little to complain about, and enjoyed debriefing our quarrels, while both recognizing our mistakes and commending our composure, on the hike back to String Lake. We returned to the van at 3:00AM and enjoyed a lovely stoveless dinner of hummus and cucumber open faced sandwiches, cubed protein bars, grapes and apple slices, before shutting eyes just after 4:00AM.

A Quick Reflection

Epics like these necessitate reflection. Obvious mistakes include underestimating the difficulty of a Grade III climb, which manifested in not packing emergency reserves of calories or water, not carrying first aid supplies or headlamps, and poor time management (we could have bailed from the tree below pitch five when we saw a wet crux pitch above). As the group leader, I also took too much time trying to free climb the crux pitch. I burned excessive daylight faffing around in the wet crack deciphering different free-climbing beta when I should have either tried to climb through the wetness efficiently (since the protection was generally good), aided the wet sections or bailed. Sometimes I get wrapped up in the glamour of “sending”, but in the alpine, not taking a dangerous fall, not putting your partner in danger and moving through the route in an efficient manner is most important. In this respect I believe I did our team a disservice.

To the contrary, the crowning correct decision was not rushing and compounding the problem. Once we topped out by twilight without headlamps or provisions we stopped, took stock of our situation and developed a plan with the resources we had. We elected to stop down-soloing once we lost light and instead resorted to rappelling, which although time consuming was much safer with only phone lights. We communicated well, moved slowly but steadily, double checked all our systems and made calculated decisions. We made sure to clean the rappel stations of all loose rocks to avoid arial assault while pulling ropes, and simul-rappelled because the terrain was steep and the rock was virgin, keeping the otherwise first rappeler safe from a loose block dislodged by the second. We made the appropriate decision to choose safety over speed, and returned to our packs entirely unscathed.

Ultimately, I don’t think “getting spanked” in the mountains will ever stop. Hell, it could happen to me again next week. Especially when tribulations are a function of discomfort rather than true danger, I try not to take them too seriously. Instead I aim to observe, listen, learn and grow, like a good apprentice.

Route Notes

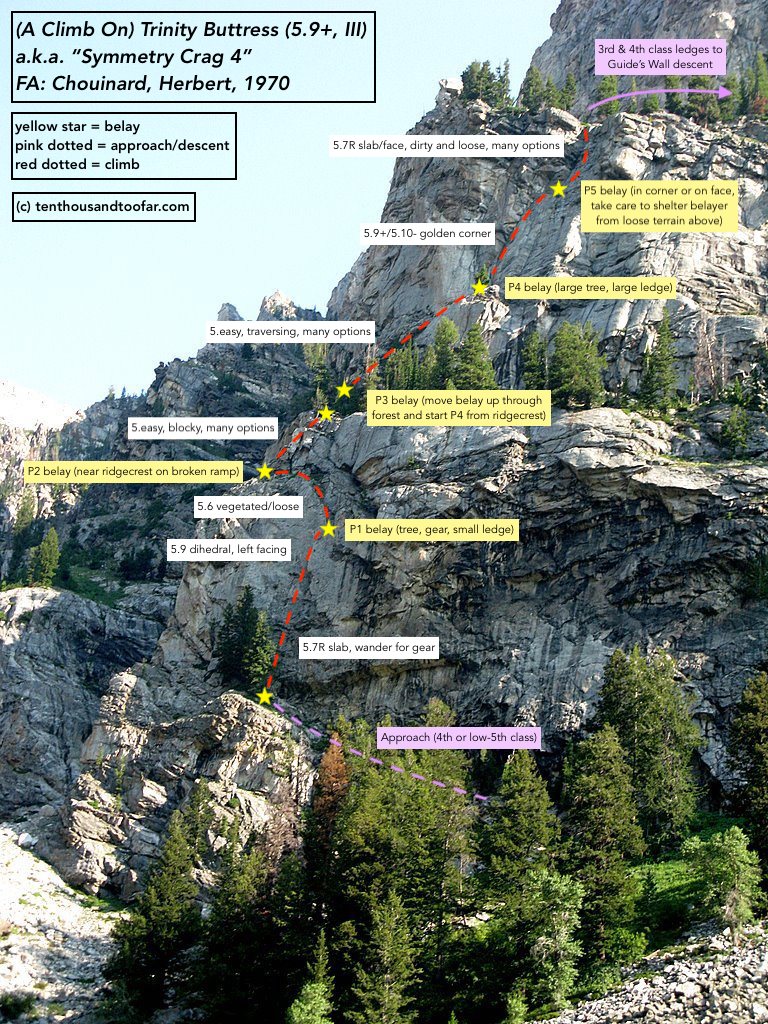

Because the descriptions on Mountain Project (MP) and in the OJ guide leave room for improvement, I have copy-pasted my own route description, location and rack recommendation from MP below. I do suggest the overlaid picture and topo from the OJ as a supplemental resource.

(A Climb On) Trinity Buttress (a.k.a. Symmetry Crag 4) – (5.9+, III)

Location – First buttress west of Guide’s Wall. We followed the Guide’s Wall approach trail and branched off when practical, stashing gear in a convenient grove of trees. The description provided in the Ortenburger-Jackson (OJ) guidebook and this post are sufficient to locate the climb. The “scrambling” required to reach pitch one is often wet, loose, and might necessitate a rope for some parties.

P1*** (5.7R, 5.9) – Spot an obvious wet facing corner from the belay and begin on a convenient tier of rock steps providing practical passage around an otherwise intimidatingly steep cave. 5.7R is fair for this pitch so long as you stay vigilant and avoid getting sucked into more difficult terrain. I down climbed and traversed around a few times, but generally just sought the path of least resistance to the base of the dihedral where protection became abundant. Climb the crack and stem the clean, steep corner to a belay ledge with a small but healthy tree.

P2* (5.6) – Seek the path of least resistance up a channeled vegetated gully trending slightly left, and be careful not to crush your belayer with a choss block. On the broad ledge above, traverse third class terrain left, towards the western ridge crest, and belay below easy broken terrain.

P3* (5.easy) – Climb easy blocky terrain to the next forested ledge. Belay where convenient, then move the belay through the forest and left, back to the western ridge crest, and belay below fourth class terrain with a large, bending tree. (OJ topo especially useful here)

P4** (5.easy) – A copy of the OJ topo is especially useful to describe this pitch, but I’ll do my best. It’s basically a very horizontal rightward traverse angling gently up along the path of least resistance to another large ledge beneath the crux pitch five golden right-facing dihedral. Locating pitch five from below the climb and having a general idea of your positioning in relation to it will help guide the way. There was a bail sling on this tree as of 6/24/23

P5**** (5.9+/10-) – A true four star pitch with a little bit of everything, and very consistent climbing at the grade. There’s no one particular crux, just continuous difficult climbing for some 40-ish meters. At the time I thought this was an old-school sandbag and definitive modern 5.10-, but the whole upper crack was seeping which could have skewed my perception. The guidebook recommends RP’s for an obvious knife-blade seam halfway up, but if you’re cool with climbing a body length or two above excellent gear the small nuts are unnecessary. I got sucked towards the roof and built a semi-hanging belay higher than recommended, adding horrendous rope drag to pitch six. I think the name of the game, according to the OJ topo, is to traverse broken slabs towards the middle of the face as soon as the difficult dihedral climbing relents, and belay in the center of the face. There is a nice small stance here with a crack-corner that will take a wide variety of gear (I believe this is the belay where the first picture is taken from (“the top of P5”)) – however, it is quite exposed (read pitch six before considering where to put this belay), so maybe it could be better to keep it free hanging in the dihedral, just lower?

P6* (5.7R) – I threw a R on this pitch because when we rolled through it was dirty as all hell with many loose blocks, mud filled cracks and a finishing chimney/gully that was actively running with water. The first half is fun airy slabbing on solid stone, but quickly devolves into nastiness. I finished climber’s left, but there seemed to be other options. There is a lot of loose rock on the angled slope above this climb and seriously great care should be taken not to shell your belayer when topping out and setting up the anchor. If you top out climber’s left there is a large tree above a mostly widow-maker free slope suitable for belay. If you top out center or right it seemed like the rope would have to run through the killer mini-talus to reach a belay. These are not recommendations – just my experience and observation – you’re on your own with this one.

Descent: Follow instructions listed above. It is possible, though NOT recommended, to rappel to the ground from exclusively trees on the east side (skier’s left) of the buttress. We did this because we started late, ran out of light and were foolishly unequipped with headlamps. It took us four double rope (60M) rappels and a bit of fourth class down-climbing on an intermediate ledge. Other bail slings indicated similar epics/errors, but this was very time consuming and surely took longer than the recommended descent.

Rack: Standard Teton 5.9 rack to three inches. Small nuts are helpful on pitch one, and perhaps some RP’s for pitch five.

Resources

- A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range, Jackson, Ortenburger (guidebook)

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Barrels & Bins Natural Market in Driggs Idaho, Range Meal Bars from Bozeman Montana and Black Diamond Equipment. Give these guys some business – who doesn’t need great skis, gear and wholesome food?

If you would like to support Ten Thousand Too Far, consider subscribing below and/or leaving a donation here. The hours spent writing these blogs is fueled solely and happily by passion, but if you use this site to plan or inspire your own epic adventure, consider kicking in. A couple bucks goes a long way in the cold world of adventure blogging. I also love to hear your thoughts, so don’t leave without dropping a comment! Thanks for the love.

Follow my photography at @brandon.wanthal.photography

enter your email to subscribe for new articles

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.

had a feeling where this day was going when you were roping up for the crux at 4pm 😅.

we all know B never shys from an epic

LikeLike

Can’t let a little darkness, thirst or starvation get in the way of a good time 😉

LikeLike