On Friday May 31st I skied the North and South Faces of Mount Bannon in a pleasant eight hour yo-yo tour from Darby Canyon. The 1,000 foot North Face is a loose West Teton “classic” with some steeper than expected pitches and a free-ride feel.

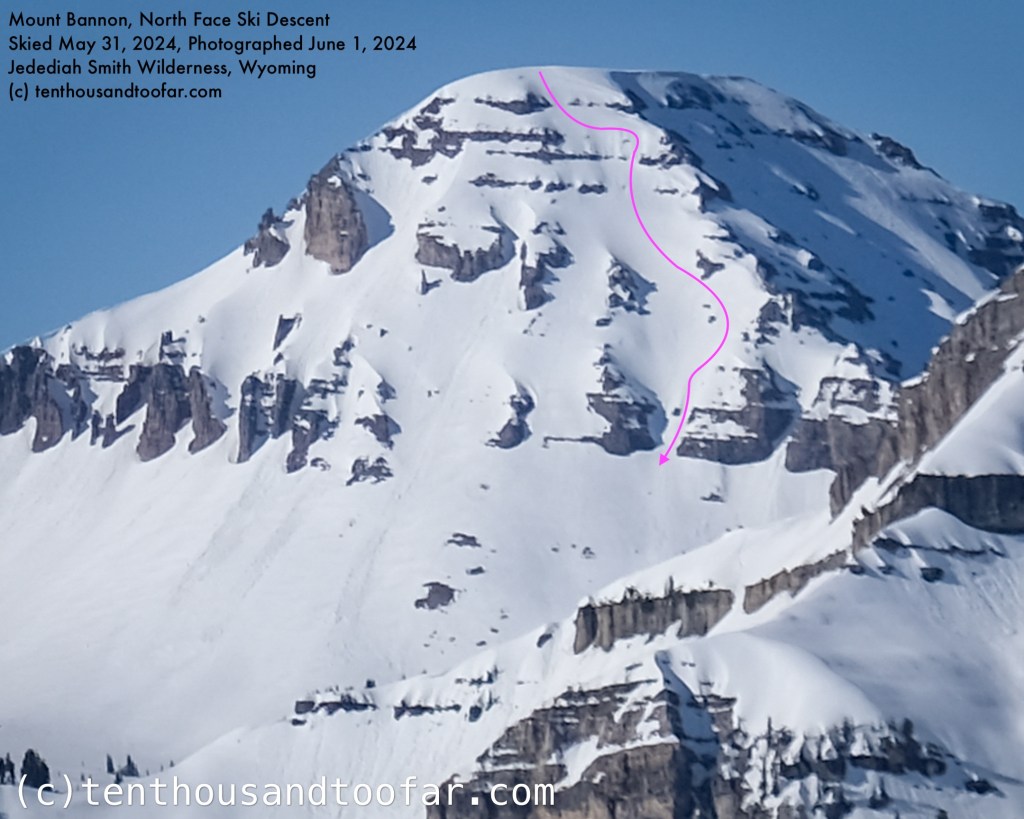

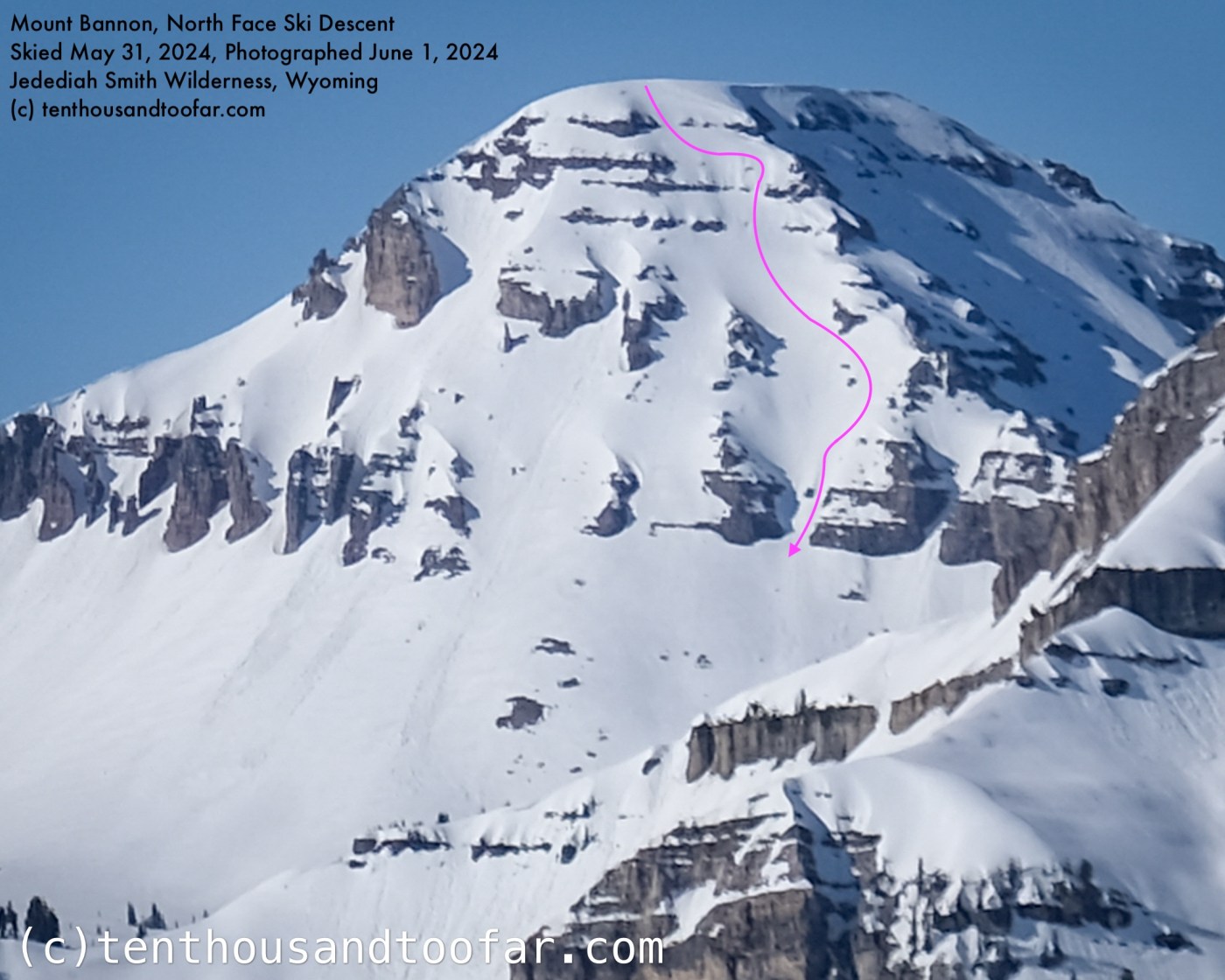

The North Face of Mount Bannon, alongside the East Face of Fossil, North Face of Housetop and some select lines on Treasure Mountain, represents the upper tier of steep skiing on the west slope of the Teton Range. These lines are distinctly different than those found on the namesake east slope peaks, and I’m no geologist, but it’s interesting to consider the underlying rock types. The west side of the Tetons contains a disproportionate amount of limestone, which tends to form open “face” ski terrain interrupted by sustained lateral bands of crumbly cliffs, some quite large. Of course, the primarily granite composition of the east slope and core range correlate with the striking Teton couloirs seen in photographs around the world. As someone who skis primarily in Grand Teton National Park – the east slope, “core range” – I am always hyper-stimulated by the quirky, terraced, atypical terrain I encounter on the few west side tours I take each year. Bannon is an excellent example. On all but the biggest years the 1,000 foot North Face will lack a defined fall line. Two sizable cliff bands, each with their own steep rollover, bisect the upper 200′, with passage made by connecting non-linear breaks with airy traverses. Once through the second cliff, an apron of fanning fingers provides three options for exit into the north fork of Darby Canyon. Though lacking in the elevation, sustained steepness and overall technicality found in the lauded core range titans, descents like the North Face of Bannon earn their salt in abrupt steepness, cryptic route finding and explicit exposure packed into an extremely condensed package. Here lies quintessential free-ride terrain, the kind of stuff you’d imagine Sammy Carlson and Nick McNutt throwing laps on for the next MSP film, close out airs be damned. But I’m a grounded bird, a carbon boot wielding ski mountaineer that rarely, if ever, takes flight. I would need a tactical approach.

Love Ten Thousand Too Far? Support independent mountain journalism with $5.10 per month through Patreon (and receive extra bonus content), or with a one-time donation. Any and all support is greatly appreciated.

I was inspired and joined by a good friend I hadn’t skied with in years, one who tours predominantly on the west slope (when in the Tetons), and following his wisdom we made an expedient approach to a sub-five hour summit. We began at the summer Darby Canyon Wind Cave trailhead, walked in tennies up the South Fork trail about three miles, and used the vague saddle just west of Fossil’s summit block to drop into the North Fork basin. From here we gained Bannon via the south face. The morning of May 31st was crisp, accentuated by a light breeze that prevented softening on the North Face despite direct sunlight since dawn. We bundled up and meandered about the summit for over an hour, catching up, snacking, enjoying expansive views and occasionally probing the face to check for softening. By `11:00AM the top few millimeters of granules had released from the frozen snowpack below, just enough for us to ponder skiing the line. Had we no time constraints we certainly would’ve waited another hour or two, but my partner had to punch the time card in town at three – time to throw down or back down.

The North Face has two pronounced rollovers that make scouting difficult from above. I was confident I could ski through the first break, but the second gave me pause. I made tentative jump turns on the firmest of baby corn into the top of the line, through the first rollover and onto the flatter bench above the second cliff. To this point I was linking turns up to 50 degrees, but the second rollover tipped beyond 50 and reverted back to barely edge-able overnight glaze. Facing some brutal exposure I opted to power-slide through the crux cliff, which was barely ski width anyways, and began making turns about 50 feet below when the angle tipped back towards sanity. A distinct sun-shade line about halfway down the face marked an instant switch to perfect spring corn, and once my brain eased from the survival zone I was able to rip fluid turns through the final crux chute and into the basin below. My partner was at the bottom waiting with a congratulatory high-five having skied around via the mellow Southeast Ridge. The deafening sounds of icy jump turns must’ve been off putting.

We retreated via ascent of the Southeast Ridge and a second bonus lap on the South Face, which is nothing more than care-free open slope skiing – the stuff of dreams. Then we reversed our approach with truly excellent corn into the North Fork basin and the entire way out the South Fork. I’m getting a bit tapped out on exposed steeps, especially in marginal snow, so I actually found the sub-30 degree basin the highlight of this day. It felt amazing to properly lay into an edge and release big carves in smooth spring snow while listening to bluegrass and swapping smiles with a good friend. Other happenings included a half dozen stunned tourists that didn’t expect to see skiers and an nefarious marmot whom dislodged a watermelon sized talus block from the southwest face of Fossil quite near our final changeover – talk about a jolt of adrenaline. As for the North Face, I’m satiated to a degree that I won’t pursue another descent, but if an opportunity with improved conditions were to cross my path I wouldn’t resist either – it’s a rad line totally worthy of the lengthy approach, if only to break up the monotony of driving 1.25 pre-dawn hours to Grand Teton National Park at the beginning of every spring adventure. I reckon the face would’ve flipped to perfect corn somewhere between Noon and 1:00PM.

Want to support? Consider a donation, subscribe, or simply support our sponsors listed below.

Ten Thousand Too Far is generously supported by Icelantic Skis from Golden Colorado, Barrels & Bins Natural Market in Driggs Idaho, Range Meal Bars from Bozeman Montana and Black Diamond Equipment

enter your email to subscribe to new article updates

DISCLAIMER

Ski mountaineering, rock climbing, ice climbing and all other forms of mountain recreation are inherently dangerous. Should you decide to attempt anything you read about in this article, you are doing so at your own risk! This article is written to the best possible level of accuracy and detail, but I am only human – information could be presented wrong. Furthermore, conditions in the mountains are subject to change at any time. Ten Thousand Too Far and Brandon Wanthal are not liable for any actions or repercussions acted upon or suffered from the result of this article’s reading.

Leave a comment